Matt Williams, Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution’s Collections Manager, was asked to create a companion ‘pop-up’ exhibition for the 2022 Victor Suchar Christmas Lecture on 19th December, delivered this year by Dr Tristram Hunt, Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum

The exhibition is replicated here for our online audience.

“I’ve chosen a small selection of objects which relate to themes reflected in the collections of the V&A, namely human creativity in the form of art and design; and hopefully to Dr Hunt’s historical and museological interests.”

Design across Cultures

These three objects from our collection are united not by purpose, material, or cultural origin, but by the geometrical abstraction of natural forms to create an attractive design. The decoration of utilitarian objects, buildings, and clothing is integral to our humanity.

An Iban Dayak ceremonial coat from Borneo

Beaded garments were worn on important ceremonial occasions – marriage, death, the opening of a new longhouse, or a successful harvest. The durability of beads offered strength and longevity to the owner, while the spirit conferred spiritual protection. Another example of this type of beaded jacket can be seen in the V&A collection here.

A North American birch-bark container with porcupine quill embroidery.

An ingenious storage solution, made by a person of mixed indigenous and European ancestry/heritage, today known as the Metis, from the Red River Colony (now Manitoba), Canada. An object with similar craftsmanship to this can be seen in the V&A collections here.

Encaustic tiles from the ruined mosque of Khargerd in the NE of Iran, close to today’s Afghan border.

These are probably from the Madrasa al-Ghiyathiyya, which was built sometime in the 15th century. There is a very fine example from the same site in the V&A collection depicted on Wikipedia here.

Loot and Museums;

an example from the Second Opium War

Throughout history it has been common for the victors of conflict to loot cities and palaces and for the centres of Empire to gather cultural objects from the territories they occupied. Many museums around the world hold objects that were originally acquired by force or through power dynamics. Such actions would now be illegal under international law and may be seen as morally indefensible. The interpretation of these objects in a museum context increasingly acknowledges this aspect of their historical background.

Ridge Tiles attributed to the ‘Forbidden City’, but probably coming from the looting of the ‘Old Summer Palace’ in Beijing in October 1860, at the end of the Second Opium War (or conceivably from the looting following the Boxer Rebellion in 1900).

These tiles are typical of ridge tiles used in the Chinese Imperial Palaces, and of a glaze that was reserved exclusively for such buildings.

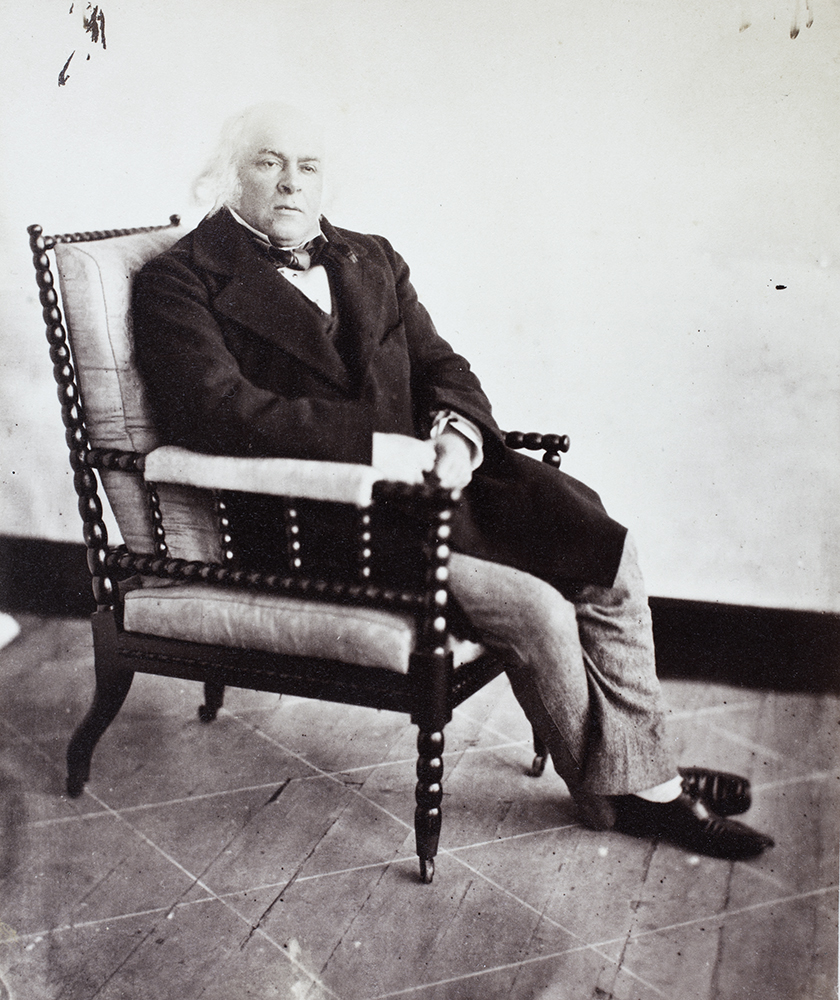

Photographs from around the time of the signing of signing the Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin) on 26 June 1858, from an album in our Vatcher-Hilditch collection. Ye Mingchen 葉名琛, (Governor General of Guangdong and Guangxi); James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin (High Commissioner and Plenipotentiary in China and the Far East); Baron Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros (minister-in-command of French troops during the Anglo-French expedition to China, aka Second Opium War).

In October 1860 Lord Elgin responded to the Chinese torture and execution of numerous European and Indian prisoners, including two British envoys and The Times journalist Thomas Bowlby, by ordering the military To destroy an Imperial Palace. Yuanming Yuan (also known as the Old Summer Palace or the Winter Palace) near Peking (Bejing) was looted and burnt by the allied English and French troops under Elgin’s command. This is probably where the ridge tiles in our collection originated.

According to historian Olive Checkland, Lord Elgin “was ambivalent about the British imperial policy of forcing trade on the peoples in China and Japan. He deplored what he called the ‘commercial ruffianism’ which effectively determined British policy responses.”

The Monmouth Rebellion

A lesser known period of political violence in English history in 1685, 34 years after the end of the English Civil War and three years before the Glorious Revolution. Also known as the Revolt of the West or the Pitchfork Rebellion, the conflict occurred mainly in Somerset, and was an attempt by a group of dissident Protestants led by James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, to depose King James II, a Catholic.

An ostrich plume reputedly worn by the Duke of Monmouth at the Battle of Sedgemoor On fleeing the battlefield at Westonzoyland, it seems he initially headed for Bristol but changed his mind and headed back south just short of Keynsham, parting company with his surgeon Dr. Oliver and swapping hats to effect a disguise. The plume was passed down through the Oliver family, and was donated by a ‘Captain Oliver’ in 1858.

Although technically a broadsword, the name “Mortuary Sword” has been given by sword collectors who consider that the decorative hilt commemorates the execution of Charles I in 1649, however many predate this event.

Another popular sword design of this period was the ‘Pappenheim’ type rapier, this German example from the early 17th century is recorded as having been found in in the roof of a farmhouse near Axbridge from whence came a number of Monmouth’s supporters.

Ecclesiastical seal matrices

For much of human history, symbolic imagery has been the key to communicating the unique identity of a person or nation, the author of a document, membership of a group, or the legitimacy and power behind a piece of currency. Ecclesiastical seals were attached to documents as guarantees of authority and authenticity.

Seals matrices of powerful individuals within the Church were usually destroyed on their owner’s death to prevent fraudulent use, so it is remarkable that this collection has survived. Their inscriptions are difficult to translate as many non-standard Latin abbreviations are used. We have no documentation associated with these examples, but it is possible to make some suggestions as to their age and origin.

This seal matrix is the oldest of the collection, being 11th or 12th century in style. It shows the Lamb of God, Agnus Dei, is symbolic of the willing sacrifice of Jesus. The inscription appears to be SG pelagii asturicen canoici, which may refer to the 7th century nobleman Pelagius of Asturias, or the Asturian bishop Pelagius of Oviedo (died 1153).

The birth of the machine age

Charles Dickens’s article from his magazine ‘Household Words’, 27 May 1854, in which he describes a visit to Colt’s London factory:

“This little pistol which is just put into my hand will pick into more than two hundred parts, every one of which parts is made by a machine. A little skill is required in polishing the wood, in making cases, and in guiding the machines; but mere strength of muscle, which is so valuable in new societies, would find no market here —for the steam engine — indefatigably toiling in the hot, suffocating smell of rank oil, down in the little stone chamber below—performs nine-tenths of all the work that is done here. Neat, delicate-handed, little girls do the work that brawny smiths still do in other gun-shops.”

Colt Navy model 6 shot percussion revolver c1853.

Following his success at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, Samuel Colt established a factory at Pimlico, London, where over 37,000 Navy Colts were produced in London between 1853 and 1856. Although entirely machine made, the pistol is engraved with scrolls and foliage and according to records is one of only 1000 engraved models that were produced.

Six shot percussion pepperbox revolver by Clough & Son, Bath, c.1850 (made by a skilled gunsmith). There is an earlier flintlock design with a rotating barrel at the V&A.