The Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution (BRLSI) is an independent treasure here to promote Science, Literature and Art to the City of Bath and now, thanks to the power of digital technology, the wider world. BRLSI is non profit making and provides world class lectures for as little as £3.00 a ticket. We provide a community hub for those interested in cultural activities and to a host of smaller cultural societies who meet in our building. As if that were not enough, we maintain a rich geographical and ethnological collection of world renown and importance. BRLSI champions Heritage projects out in the wider community and hosts visiting art exhibitions. You might wish to find out more about our fascinating history below!

About Us

Our History

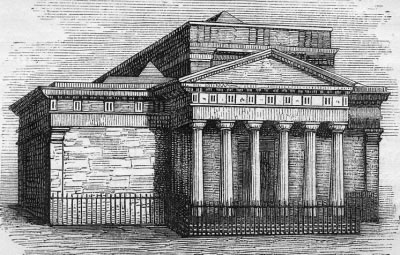

In the 19th Century some prominent residents proposed that a permanent Literary and Scientific Institution be created in Bath. In 1824, after a devastating fire had destroyed Bath’s lower assembly rooms, the first incarnation of the BRLSI was set up on Terrace Walk. The initial site, elegantly designed by George Allen, was spacious enough to accommodate the Institution’s vast collection of Roman antiquities, expensive books and geological specimens. Bath at this time was considered to be the home of geology. Such was the sudden prestige of the Institution that in 1830 the man who was later to become King William IV conferred royal patronage on the Institution and in 1837, under Queen Victoria, the Royal was added to the Institution’s name.

In the 1850s the public’s curiosity for natural history saw the founding within BRLSI of both a Geological Museum and Natural History Museum. Original photographs exist of BRLSI in its premises at Terrace Walk and they are breathtaking.

Plans to renovate the Terrace Walk site were met with frustration because of a new road building scheme in the centre of the city that made a compulsory purchase necessary. Consequently, in 1932, new premises were taken up in BRLSI’s current site at Queen Square – a site, incidentally, where the house of Dr William Oliver, eminent Physician and co-founder of the Mineral Water Hospital, once stood.

The premises were perfect but another obstacle in BRLSI’s fortunes arose when, during World War II, the Institution’s headquarters in Queen Square were requisitioned and used by the Admiralty until 1959, when the institution’s assets, including the building, were transferred to Bath City Council. Many of the museum objects were put in storage during the war and others were transferred to other museums. The BRLSI was in hibernation.

So how is it that we recently celebrated the 25th anniversary of the re-establishment of BRLSI? In 1988 the Friends of BRLSI steering group, who had not given up on the institutions fortunes, fostered hopes for a revival and their efforts resulted in their acquiring trusteeship in 1993. A re-launch exhibit in 1993 attracted much public interest and for the first time in over 50 years new members were enrolled.

Incrementally, the BRLSI as we know it today evolved. What started off as a setting for social events for the like-minded gradually evolved into the home of a world class lecture programme and a collection rich in a diverse number of areas. These areas include archaeology, zoology, mineralogy, botany, ethnology and paleontology. BRLSI also has a historic library which encompasses exploration, history, philosophy and religion.

BRLSI’s mission to provide a cultural hub for the people of Bath and the surrounding area is served further by the provision of a home for Local Nature Studies and for many like-minded groups such as the Jane Austen Society and the Gaskell Society. Each year the Bath Shakespeare Society hold their annual celebration to mark Shakespeare’s birthday in the Institution’s Elwin Room. BRLSI also rent out rooms at a discount to groups sharing the Institutions charitable and educational ethos. And if that was not enough, BRLSI hold weekly coffee mornings for those with a passion for the arts and sciences.

And BRLSI is still growing! Always looking for further ways in which to deliver their mission to provide the people of Bath with new stimulus and a platform for debate. As BRLSI pass the 25th anniversary of their re-opening and negotiate another interesting fork in the road in terms of a global pandemic, they take the spirit with which their founding fathers set up their initial home in 1824 to make sure it is relevant for the 21st century. Digital platforms enable our programme and collections to reach you wherever you may be sat in the world; in addition, digital apps bring that same collection to life and broaden access to treasures that once sat buried to all but those in the immediate vicinity.

In this section you will find information on Key figures and forerunners of the BRLSI located in Bath, from 1777 to 2002:

BRLSI is a Literary and Scientific Institution today, but its forerunners in Bath had much wider interests, with Agriculture at the forefront. The following extracts from our Archives give some details of this undertaking.

The Circus, Bath, designed by John Wood the Elder and completed in 1762

The Bath Chronicle for 28th August 1777 carried a notice addressed to “The Nobility and Gentry in the counties of Somerset, Gloucester, Wiltshire and Dorset in general, and the Cities of Bath and Bristol in particular”. This was a proposal for the “Institution of a Society in this City, for the encouragement of Agriculture, Planting, Manufactures, Commerce, and the Fine Arts…”.

Interested individuals concerned with forming such a society are invited to attend a meeting at 11 a.m. on September 8th at York House (now the Royal York Hotel). Twenty-two people responded to the notice and the first of Bath’s scientific societies was inaugurated. It was to continue its close associations with Bath until 1974, when its administration moved to a new, permanent home at Shepton Mallet.

The idea of a society was the brain-child of Edmund Rack, the son of a Norfolk labouring weaver. A draper by trade, Rack had also cultivated a taste for literature. During his earlier life in Norfolk he had become very interested in agriculture and, in particular, in the application of modern methods and when, in 1775, he settled in Bath, and his attention was immediately drawn to the poor standard of agricultural practice in the West Country.

Rack was responsible for a series of letters to the Farming Magazine and the Bath Chronicle, pointing out that it was in the interest of the farmer, the landowner and the nation in general that the agricultural resources of the country should be increased. By August 1777 he must have felt that the time was ripe for more specific proposals, hence the advertisement.

At the inaugural meeting the Chair was taken by John Ford. The attendance was as follows:

John Ford Esq. in the chair,

Revd. Dr. Wilson Phillip Stephens, Esq.

Revd. Mr Ford Paul Newman Esq.

Dr. Wm Falconer

Mr. John Newman

Dr. Patrick Henley

William Street Esq.

Wm. Brereton Esq.

Mr. Symons, Surgeon

Mr. Saml. Virgin

Mr. Crutwell, Surgeon

Mr. Richard Crutwell

Mr. Arden

Mr. Foster, Apothecary

Mr. Wm Matthews

Mr. Cam Gyde

Mr. Parsons

Mr. Benj. Axford

Mr. Edm. Rack

Mr. Bull

Edmund Rack

Several resolutions were passed, among them the unanimous request that Edmund Rack, then 42 years of age, should be appointed Secretary of the Society.

The first edition of Aims, Rules and Orders of the Society, published in 1777, lists several important objectives. These include the aim to improve husbandry through the award of premiums (prizes) and the encouragement of experimentation in those spheres most needing it.The first General Meeting on 9th December 1777 considered 49 recommendations for premiums ranging from 1 guinea to 30 for projects as varied as the raising of the principal farm crops, the rearing of agricultural stock , improving farm implements, softening hard water and even the manufacture by a woman of the greatest quantity of black lace.

Each subsequent year brought new projects for premiums, some of them decidedly unexpected. In the 1809 list, for example, there is the offer of an award for the best treatise either in defence or refutation of the theory of the Rev. Mr. Malthus concerning population; the prize-winning essay was published the following year. Unlikely though this topic sounds in its particular context, it of especial interest because Malthus himself had strong connections with Bath. One source actually states that he spent the last four years of his life at Bath, though this is uncertain. It is known, however, that he died there in 1834 at 17, Portland Place, the home of his father-in-law, John Eckersall. He is believed to have been buried at Claverton. At a later date a tablet was erected to his memory just inside the West Door of the Abbey Church.

By the spring of 1780 a site had been found and approved by Edmund Rack and ten acres of land at Weston, Bath, was taken over for experiments in agriculture. The land itself which presented a variety of soils and situations, was part of a farm occupied by a Mr. Bethel, who agreed to conduct the experiments himself, under the supervision of a committee.This was the very first experimental farm in Britain and a worthy precursor to Woburn and Rothamstead. Even so, after about ten years the scheme petered out, probably as a result of defective management.

MIneral Water

Beside Edmund Rack, there were other interesting individuals among the earlier members of the Society. William Falconer, a Doctor of Medicine of both Edinburgh and Leyden Universities, came to Bath in 1770, taking up residence in the Circus. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1773 and later became a physician at the Bath General Hospital. One of his particular interests was the medical applications of the Bath hot mineral spring water, a subject on which he wrote several works. William Matthews, another founder member, and later to succeed Rack as Secretary, was the son of an Oxfordshire Quaker shoemaker. He came to Bath in 1777, first setting up a brewery, then a coal yard and then a seed and implement business at Hetling House (now Abbey Church House). He published several books, all of them on theological or moral issues.

Soon after the Society’s inauguration, Thomas Curtis became a member. The original founder of the first Bath Philosophical Society in 1779, Curtis was a greatly respected figure. In an obituary Edmund Rack said of him “he was well read in men as well as books; yet he rather sought to be useful rather than popular; to merit rather than court applause”.

Joseph Priestley (Image: Wikipedia)

More important historically was Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen. It is perhaps surprising to find Priestley associated with Bath; he is almost invariably linked with Birmingham where his house and laboratory were once pillaged by a mob in an orgy of political violence. Between the years 1773 – 1780, however, he was a library companion to Lord Shelburne, afterwards First Marquis of Lansdowne and in 1782, Prime Minister. Priestley lived near Lord Shelburne’s seat at Bowood near Calne, Wiltshire. In fact it was at Calne that he discovered oxygen, a momentous event in the development of chemistry. In 1777 we find Priestley as Honorary and Corresponding member of the Society. In 1778 he was Vice-President and in 1780, on the Committee of Correspondence and Enquiry.

It is clear from a number of sources that Priestley was active in both the social and the scientific life of Bath. His introduction to its scientific life was probably through William Watson, with whom he was already acquainted. In the preface to Watson’s only book, A Treatise on Time, published in 1785, tribute is paid to “that eminent philosopher, Dr. Priestley (who thought it [the book] not unworthy of the public eye)”.

Sir William Herschel

Priestley also knew William Herschel. At one stage he assisted Herschel in making the acquaintance of John Mitchell of Derbyshire, who was also engaged in the construction of large astronomical telescopes. On the social side, Priestley was friendly with the Linleys of Bath and at one time lodged with them.

Letters and Papers

In 1780 came the first volume of Letters and Papers of the Society, the forerunner to today’s BRLSI Proceedings. These appeared irregularly and terminated with Vol. XV in 1829. They provide an invaluable source of information on the startlingly wide range of activities carried on within the Society. On reflection this is not really surprising. The era of specialised national journals was still to come and local society journals, with their wide spread of information, formed a necessary step in the evolution of the present-day serial. Articles in Letters and Papers, and later in the Journal, produce such topics as meteorology, the exhibiting of livestock, hay steaming, the chemical analysis of soils and later on, even steam engine trials.

A recurring theme in the Society’s earlier publications was the application of chemistry to agriculture, especially chemical analysis of soils and fertilisers. As early as 1805 the Bath Society had voted funds to establish a chemical laboratory. In the same year, Dr. Clement Archer, a Bath physician, offered to lecture without fee, on this same topic of chemistry’s applications to agriculture. He also offered his services in superintending the operation of the analytical laboratory – an offer which was promptly accepted “and the Doctor was immediately appointed Chemical Professor to the Society, with the unanimous thanks of the Meeting”.

The laboratory was set up in the vaults of Hetling House; £100 was to be spent by Dr. Archer, presumably on equipment and chemicals, and £50 per annum to be paid to Mr. Cadwallader Boyd, as assistant. The following spring, Dr. Archer gave a course of lectures “which were attended as well by many Ladies and Gentlemen who had a taste for science, as by most of the members who remained in town”. Unfortunately, Dr. Archer died after a few months but the Institution continued in the hands of Boyd, ” a very ingenious and intelligent chemist whose real knowledge and acquaintance with the science is accompanied by that unassuming modesty generally attendant on true merit”.

Referring to the quality of Boyd’s analytical work, we read in Letters and Papers that “of the accuracy of the results of these analyses as delivered by Mr Boyd, the Society entertains not the least doubt”. Clearly the Society had great faith in Boyd! A present-day assessment of his methods would provoke considerably less optimism. The methods he used were those of Humphrey Davy, as published in his Elements of Agricultural Chemistry. Davy, later Count Rumford, was, as we all recall, the man who first isolated sodium and potassium, an event recalled in the clerihew by Edmund Bentley:

Sir Humphrey Davy

Abominated gravy

He lived in the odium

Of having discovered sodium

Great chemist he may have been, but his analytical methods were not particularly reliable.

Agricultural Science

As might have been expected, the first half of the 19th century saw tremendous developments in the science of agriculture. Chemistry and physics were undergoing rapid changes and it was only natural that the newly acquired knowledge should be applied to biology, which, after all, depended on the same basic mechanisms.

Probably the single most important step taken by the Society was the appointment of Dr. Augustus Voelcker as its consultant chemist in 1855. His influence was strongly felt in several areas. Through the Society’s Journal he brought the new agricultural science directly to its membership; he travelled extensively through the entire area covered by the Society, giving lectures and taking part in discussions; he analysed soil and fertiliser samples given to him by farmers and he was able to advise them on their particular needs, as well as the value of their fertilisers. As he put it, “any good analytical chemist can ascertain the exact amount of the different constituents of the manure, and, knowing the market price at which they can be obtained separately, he is enabled to calculate with tolerable accuracy its commercial value”. There was certainly need for such information for at this time the adulteration of foodstuffs had reached extreme proportions.

A parallel situation existed in the sale of fertilisers. Voelcker drove home the basic point that these should be analysed and that “the presentation of a chemical analysis by the dealer is in itself no guarantee of the genuiness or value of the manure”.

Voelcker had been educated in Germany, where he studied under Liebig. In 1849 he was appointed the first Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester. Despite his German origins, he appears to have been popular with English farmers. His emphasis on checking fertilisers by analysis paid off; within a few years the Society noted a marked improvement in the quality of fertilisers offered for sale. In 1863 he resigned his post at Cirencester and set up in private practice in London but he still maintained his association with the Bath Agricultural Society.

Another side of agriculture which interested Voelcker was cheese making. Here too, he stressed the scientific approach – “All that is mysterious about it is purely accidental”. Improvement in the quality of cheese and butter was a matter which concerned the Society increasingly in the latter part of the 19th century. In 1889 its first Cheese School was set up in Wells, with the complete course lasting four weeks and costing 8 guineas. Later it moved to Frome with F.J. Lloyd, an agricultural chemist in attendance. In spite of these praiseworthy efforts, reports in the Journalistic pointed to the superior quality of foreign produce. The reason was claimed to be insufficient agricultural education and research.

In 1852 a decision was taken to move the Annual Meetings away from Bath and to hold them each year in a different town within the Society’s area. Each meeting was combined with an Agricultural Show. The mid-20th century saw the far-reaching decision to seek a permanent site for the Annual Show and, accordingly, a 200 acre site was acquired at Shepton Mallet. In 1974 the Society’s administration too, left its permanent home in Bath and moved to Shepton Mallet. After 197 years the connection with Bath was almost, but not quite severed. All that remained to the City were the Society’s Library, now housed in the University of Bath, and its archives, which were given into the care of Bath City Council. Very likely Edmund Rack would have approved!

Mostly taken from: Bath Some Encounters with Science (Chapter Four: Societies and Institutions), W J Williams and D M Stoddart, Kingsmead Press, 1974.

Additional material and Editing, Joy Whalley, Ruth Abbott. Also used: The Revival of the Institution, Jane Coates and Michael King, BRLSI Annual Report,1996.

Alongside the Agricultural societies, ‘Philosophical’ societies appealed to those particularly interested in the newly emerging field of science. Bath had one of the first, but it took four attempts to create one that lasted – the Bath Literary and Scientific Institution, which needed a disastrous fire in one of Beau Nash’s favourite haunts to give it a purpose-built home.

The formation of the Bath Agricultural Society in 1777 was by no means an isolated incident. By the middle of the 18th century similar societies were being formed throughout the country. In some respects they highlighted the isolation felt by the intellectual or, more particularly, the scientifically inclined. They became meeting places for the sharing of mutual interests As well as the agricultural societies there were others which leaned rather more towards the newly emerging science than towards technology. By far the most important was the Royal Society of London founded in 1660; another significant one was the Lunar Society of Birmingham (c 1765 – 1791), so called because it met monthly around the time of the full moon, in order that members could have some light on their way home. These institutions were often known as Philosophical Societies, and the Bath Philosophical Society was one of the earliest.

The Bath Philosophical Society’s foundation can be attributed to Thomas Curtis. A Governor of the Bath General Hospital, he was already a member of the Agricultural Society. On 27th December 1779 he suggested to Edmund Rack “the Establishment of a select Literary Society for the purpose of discussing scientific and Phylosophical subjects and making experiments to illustrate them.”

As early as the 28th December 1779 the Society was formally established and within days a set of rules had been agreed upon. These included the schedule of meetings – on Friday evenings, once a week in winter and once a fortnight in summer. One interesting feature was the restricted membership; the maximum number of members was fixed at 25, with election by ballot only. Members were at liberty to discuss “the Arts and Sciences, Natural History, the History of Nations or any branch of Polite Literature”, but not “Law, Physic, Divinity and Politics”. Edmund Rack, already Secretary to the Agricultural Society was also elected Secretary to the Philosophical Society.

Edmund Rack

Like the Agricultural Society, the Philosophical Society was concerned to build up a collection of books. In addition, the rules stipulated that, when funds were available, instruments should be purchased for experimental work house in Milsom Street was subsequently used for this purpose.

Hugh Torrens has compiled a list of the original members which is reproduced below:

Members of Bath Philosophical Society (1779 – 1787)

1. Hon. Hugh Acland (1728-1805)

2. John Arden (1702-1791)

3. Mr. Atwood

4. Charles Blagden (1748-1820)

5. John B.Bryant (fl 1779-1792)

6. James Collings (c 1721-1788)

7. Thomas Curtis (c 1739-1784)

8. William Falconer (1744-1824)

9. John Henderson (1757-1788)

10. William Herschel (1738-1822)

11. John Coakley Lettsom (1744-1815)

12. John Lloyd (1749-1815)

13. Mathew Martin (1748-1838)

14. William Matthews (1747-1816)

15. Constantine John Phipps (Lord Mulgrave) (1744-1792)

16. Caleb Hillier Parry (1755-1822)

17. Thomas Parsons (1744-1813)

18. Joseph Priestley (1733-1804)

19. Samuel Pye

20. Edmund Rack (1735-1787)

21. Rev. Samuel Rogers (1731-1790)

22. Benjamin Smith (fl 1779-1807)

23. John Staker (c 1731-1784)

24. John Symons (died 1811)

25. John Walcott (1755-1831)

26. John Walsh (1726-1795)

27. William Watson (1744-1824)

William Watson

It is noted that the list is in excess of the maximum number of 25. Comparison with the list of founder members of the Agricultural Society shows that several people were members of both. A remarkable feature of the list is that no fewer than eleven members were, or became, Fellows of the Royal Society, London and ten featured in the Dictionary of National Biography.

There are few printed records of the Society and it published no papers or journals, but we can glean some indication of its activities from several sources. One of these is Edmund Rack’s journal A Disultory Journal of events at Bath. This notes the attendance of Dr. Priestley on 22nd March 1780.

On 31st December 1780 Rack comments “this institution promises much rational improvement and instruction; and has a much more favourable beginning than the Royal Society in London had 100 years ago – there being only five members for more than two years: and those 5 not superior in learning and genius to most of our members”. On another occasion he reports the presence of Mr.Herschel – “optical instrument maker and mathematician”.

William Herschel

Not all members of the Society lived in Bath; for example, Messrs Blagden, Lettsom, Walsh Phipps and Priestley were none of them strictly “local “. A number of members were medical men by training but who widened their interests to include a much broader range of activities.

John Arden was the roving populariser of science, always ready to lecture on scientific topics for a fee. Product of the age, he was responding to the sudden outburst of scientific and technological activity which started in the 17th century and which we now recognise as the beginnings of the modern scientific revolution. The public imagination had been caught by this new subject. Scientific and technological encyclopaedias, popular books and public lectures abounded and it was in the latter sphere that Arden really came into his own.

William Watson, as we mention elsewhere, had a considerable influence on Herschel. Although he did not live in Bath, Charles Blagden F.R.S. was an important member of the Society, submitting papers and forming an important link with the main stream of British Scientific work. As Secretary to the Royal Society, London and a former personal assistant to the great chemist Henry Cavendish (who discovered hydrogen), Blagden was an influential man in the world of science.

The Bath Philosophical Society came to an end in 1787, the year of Edmund Rack’s death. Hugh Torrens speculating on the reasons for its demise concludes that a major cause was fragmentation due to members leaving the neighbourhood. Herschel, one of its most active members, (he contributed 31 papers, one of them on the discovery of Uranus) moved to Datchet in 1782; Priestley moved from Calne to Birmingham in 1780. Two of the original members, Curtis and Staker,died in 1784. An attempt was made to reconstitute the Society in 1799 – Watson and Herschel were elected members – but the new Society soon petered out. In 1815 there was a third attempt to form a Bath Philosophical Society, this time under the inspiration of Charles Hunnings Wilkinson, a geologist and friend of William Smith. Like its predecessors, it too failed. The fourth society, the Bath Literary and Scientific Institution, was the most successful; its origins were more complex and its aims were more broadly based.

Birth of the BRLSI

The first stirrings of a movement towards the foundation of a literary association were felt, naturally enough, among the educated members of the community. Bath cannot be said to have played a pioneering role, possibly because the existence of the assembly rooms, clubs and booksellers went a long way to disguise the city’s need for a library of classics and a cultural centre for the studious. However January 1801 saw the birth of a plan to found a “Bath Publick Library” of learned books not usually found in circulating libraries or private collections. The president of the proposed library was Sir George Colebrooke, its treasurer, Mr. William Matthews, its secretary Dr. George Gibbes and its librarian Mr. John Browne; the committee of 20 was dominated by the Church and the medical profession. The scheme was doomed to failure; Bath did not number sufficient wealthy permanent residents to subscribe to such a library and the project sank, almost without trace.

In 1812 the Rev. Joseph Hunter, remarking that he found it necessary to journey to Bristol for his books, produced a further plan for a “better public library than any then existing”, but this too met with no success.

In 1819 a Bath physician Dr. Edward Barlow, produced a circular letter and inserted notices in the local press inviting interest in an institution offering facilities for a library and reading room, a botanic garden, a museum of natural history, a cabinet of mineralogy, a cabinet of antiquities, a cabinet of coins and medals, a hall for lectures and a gallery to exhibit paintings and sculpture. To build this would need £30,000, to be raised in £50 share units. The Rev. Hunter expressed misgivings about such a sum being raised but purchased his share and was elected “member of the Board of Directors of the Bath Institution”. The Board met monthly and added several new members but the money did not appear and they had to rethink their scheme radically. By 1820 less than £4,000 had been subscribed and both Dr. Barlow and the Rev. Hunter proposed greatly reduced alternative schemes.

It was a disastrous fire in the Lower Assembly Rooms on 21st December 1820 which finally got the scheme on its way. The building, at Terrace Walk near the Parade Gardens, had originally been Harrisons Assembly Rooms, one of the favourite haunts of Bath’s Master of Ceremonies, Beau Nash, in the early 18th Century. It belonged to Earl Manvers, who generously offered to erect a new building on the site and to rent it to the Institution. In 1823 money was still short but plans went ahead; a trust deed was prepared and a lease of the premises was granted by Earl Manvers to a committee of “friends”, one of the most noteworthy being Mr. Francis Ellis.

Engraving of the first BRLSI building at Terrace Walk, Bath.

On 19th January 1825 the rooms were opened to subscribers and the Bath Literary and Scientific Institution was in being. The first annual report, published in 1826, named Henry Woods F.L.S. – a zoologist, who also published papers on Bath fossils – as secretary and William Lonsdale, a geologist, as curator. In 1830 it received royal patronage from the Duke of Clarence (later William IV), and in 1837 became the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution when when Queen Victoria continued patronage.

The Institution’s chief activity for the first 15-20 years of its existence was in offering a series of lectures at £1 for a series of 8 or 3/- for a single lecture (prices which in those days would have excluded all but the comparatively wealthy). Enthusiasm waned and after 1840 the lectures from visiting celebrities were changed to fund-raising events given by members. By 1848 it was clear that the members would either have to increase their income somehow or give up their premises. In 1852 there was an attempt to form a genuine public library in the City and there were suggestions that the Institution should either transfer its books to this or even transform itself into a rate-supported body.

A letter in the Bath Herald of 26th February 1853 asserted that the Institution had fallen down on its aims, that its reference collection was moribund and that its lecture rooms were empty; if it would open its doors to the public and accept rate support, it would be doing the city a favour. In spite of its dire financial straits, still a motion that the Institution should combine with other bodies was defeated. Once again it was saved by the generosity of an individual, Mr. William Tite, M.P. for Bath from 1855 until his death in 1873. Through him the Institution was enabled to buy its premises outright and during the 1860’s it enjoyed a slight improvement in its affairs. The year 1899 saw an amalgamation with the Bath Athenaeum which had been set up as the Mechanics Institute in 1825 but had changed its name twenty years later.

BRLSI’s building at 16-18 Queen Square, Bath.

The modern BRLSI

In 1932 the Institution was forced to moved to new premises at 16-18 Queen Square, after its building in Terrace Walk was compulsorily purchased to make way for a road scheme. Unfortunately its new premises were requisitioned by the Admiralty in 1940 (like many buildings in Bath) and occupied until 1959, by which time the Institution was considered defunct.

In accordance with the Trust Deed of 1859, the building and other assets were transferred to Bath City Council “for the advancement of Literature, Science and the Arts in the City of Bath” The buildings were used to house the City Reference Library, the Geology Museum and a Reading Room. In 1968 the Institution was registered as an educational charity.

In 1974 with local government re-organisation Avon County Council took over control of the assets causing local concern about their future. This led a group of people to consult the Charity Commissioners; the BRSLI Steering Committee was set up in November 1987, and the Friends of the BRSLI in February 1988. In April 1992, on the Charity Commission’s advice, Shadow Trustees were appointed (3 from the Friends, 3 from the Bath Society working party, and 3 from the University of Bath), and in 1993 Avon County Council approved their Forward Plan and the transfer of the Trusteeship them. A Relaunch Exhibition was held in May 1993 at which the first new members for more then fifty years were enrolled.

A Company, Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution Trustees was incorporated and in September 1993 the Trusteeship of the charity and the ownership of the buildings was transferred to them. Part of the building was leased to Bath Training Services in return for a substantial contribution towards its restoration and by March 1995, the Institution was able to return to its own premises.

Mostly taken from: Bath Some Encounters with Science (Chapter Four: Societies and Institutions), W J Williams and D M Stoddart, Kingsmead Press, 1974.

Additional material and Editing, Joy Whalley, Ruth Abbott, Paul Stephens. Also used: The Revival of the Institution, Jane Coates and Michael King, BRLSI Annual Report,1996.

This brief history is taken largely from notes compiled by former curator, Diana Smith, with some additions from the re-launch catalogue written by her successor, Roger Vaughan. An overview can be obtained from Innovation and Discovery – Bath and the Rise of Science, edited by Peter Wallis (2008), available from BRLSI and local bookshops.

Bob Draper, with later additions (1987 onwards) compiled by Jane & John Coates.

1777 Society formed by Edmund Rack “for the encouragement of Agriculture, Planting, Manufactures, Commerce, and the Fine Arts”. Now the Royal Bath and West of England Agricultural Socierty, its historic library is housed at the University of Bath and its archives at the Record Office in the Guildhall, Bath.

1779 Bath Philosophical Society formed (by members of the Agricultural society, with Rack as secretary) to discuss “The Arts, Sciences, Natural History, the History of Nations or any Branch of Polite Literature but not Law, Physic, Divinity and Politics”. The Society was dissolved in 1787 due to members’ deaths and others leaving the neighbourhood.

1799 The Society was revived but disbanded again in 1806.

1815 Another attempt was made to form a philosophical society; this time it lasted about four years. It led to the establishment of the Mechanics Institute which later became Bath Athenaeum.

1819 Moves were made by Dr. Edward Barlow to form an institution with a library and reading room, a botanic garden, a museum of natural history, a cabinet of antiquities, a cabinet of coins and medals, a hall for lectures and a gallery to exhibit paintings and sculpture: Bath Literary and Scientific Institution.

1820 The Lower Assembly Rooms on Terrace Walk were destroyed by fire, with the exception of Wilkins’ portico. Earl Manvers agreed to finance a new building and lease it to the Institution.

1822 G.A. Underwood – architect and surveyor, drew up plans for a grand new building to include a museum, exhibition room, library, laboratory and lecture room with an entrance on North Parade, reinstating the portico.

1824 Bath Literary and Scientific Institution established.

1825 On 19th January the Institution was opened with the Duke of York as Patron, the Marquess of Lansdowne as President.

1830 Institution received royal patronage from the Duke of Clarence (later William IV).

1837 The prefix “Royal” added when Queen Victoria continued patronage.

1850 Rev. Leonard Jenyns moved to Southstoke near Bath, from Cambridgeshire.

1853 Charles Moore moved to Bath and offered to deposit his already large and important geological collection with the Institution.

1855 Bath Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club was founded by Leonard Jenyns, with fellow naturalist Christopher Broome, Charles Moore and Harry Scarth, the antiquarian, as founder members. It organised field trips and held lectures at the BRLSI, publishing its proceedings from 1857 until its dissolution in 1911.

1858 The Institution purchased its building.

1859 Trust deed drawn up which included the statement that: “…in the case of dissolution of the Institution as above constituted, the property as well as the building shall be vested in the Mayor and the Corporation of Bath….for the advancement of Literature, Science and Art in the City of Bath…”

1864 Annual Conference of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held in Bath. Charles Moore was local secretary and the Institution was host to many of the events. Charles Moore’s collection and scientific knowledge were acclaimed by many of the visiting scientists.

1867 Duncan Memorial Fund established. Five hundred pounds invested. It produced twenty four pounds per annum in interest to be devoted to the improvement of the library and museum.

1869 Leonard Jenyns presented his library and herbarium to the BRLSI on condition that a separate room be found for them and that they be kept distinct from other collections, and on dissolution of the BRLSI the items be returned to him or his heirs instead of being disposed of in any other way.

1881 Death of Charles Moore. Appeal launched to purchase his collection which was valued at one thousand one hundred pounds. The appeal raised £1,207 4s.6d. The balance was used for a commemorative plaque.

1883 Rev. H.H. Winwood appointed Honorary Curator.

1886 Christopher Broome bequeathed his important botanical library and herbarium to the Institution.

1890 Trust Deed altered to permit a mortgage for essential repairs to be made to the building.

1893 Death of Leonard Jenyns.

1899 Bath Athenaeum amalgamated with BRLSI as their building was due for demolition.

1920 Death of H.H. Winwood.

1925 Institution was not in a fit state to hold centenary events. A special fund raised enough money for repair work. Dr F.S. Wallis, curator of Bristol Museum, started to re-catalogue the Moore collection.

1932 The Institution moved to 16-18 Queen Square as a road improvement scheme entailed the demolition of the Terrace Walk building (see The original BRLSI building). Wallace had to pack up, move and re-display all the collections.

1940 The Queen Square premises were requisitioned by the Admiralty. All the displays were dismantled and and the collections and the books stored elsewhere: the books to St. Catherines Court near Batheaston, and the fossils were taken Bristol.

1959 Premises vacated by Admiralty. However the Institution had ceased to function so it was resolved that: “…the Institution shall be dissolved and that all the property shall be vested in the Corporation for the advancement of Literature Science and Art in the said City of Bath.

1960 Collections returned from various wartime stores. Decision taken not to redevelop the Museum but to alter the building for use as a City Reference Library. Ron Pickford, employed as a joiner, and a keen amateur geologist, prevented material from being discarded. A great deal of material was however loaned to other museums, loaned to schools, given away or sold.

1964 Bath Reference Library opened to the public.

1967 Bath Geological Society founded.

1968 BRLSI registered with Charity Commission as an educational charity. Also Ron Pickford formally appointed Curatorial Assistant and a space for displays made available on the second floor. New displays were mounted in consultation with Mr. Bob Whitaker of Bath Geological Society. He continued in a consultancy capacity until 1974.

1974 With Local Government Reorganisation, Trusteeship transferred to the newly formed Avon County Council (Education Dept.).

1978 Trusteeship passed from the Education Dept. to the Community Leisure Dept.

1982 Charity Commission prevented Avon County Council moving library administrative offices into Queen Square premises, after representations from the Bath Society and Bath Geological Society.

1985 Ron Pickford retired. He was a Fellow of the Geological Society of London and the Geological Curators’ Group made a presentation to him in honour of the work he had done in Bath.

1986 Diana Smith, previously geologist for Norfolk County Museums Service, appointed Curator.

1987 Discussions continue on the transfer of Trusteeship with a letter from five concerned individuals to the Charity Commission about the transfer of Trusteeship and the state of the collections.

1987 This group formed themselves into the BRLSI Steering Group in November to continue to press their concern about the collections. Others sought legal advice on the propriety of events in the light of the terms of the Trusteeship.

1988 The Friends of BRLSI was formed in February 1988 to support the general aims and to foster the revival of the Institution itself, and The Bath Society set up its own working group to consider the future of the BRLSI.

1992 In April, with the encouragement of the Charity Commission, a body of Interim or Shadow Trustees (3 drawn from Friends of the BRLSI, 3 from The Bath Society Working Party and 3 from the University of Bath) was set up, with the authority of Avon County Council, to work out realistic aims, plans and the financing for a revived BRLSI. In November the Interim Trustees submitted a Forward Plan to Avon County Council.

1993 Avon County Council, having already embarked upon setting up a combined lending and reference library in the new Podium building and therefore about to vacate the BRLSI premises at 16-18 Queen Square, approved the Forward Plan and the transfer of its Trusteeship of BRLSI to the Interim Trustees.

A re-launch exhibition was held in the premises in May. The first new Members for 50 years joined the Institution. An agreement was negotiated with Bath City Council for the short term use by it of part of the premises and, with the Area Museums Council for the South West, the Council agreed to fund the employment of a Development Officer for three years.

BRLSI Trustees were incorporated on 27 September 1993 as a company limited by guarantee and, through the Charity Commission, the Institution and the freehold of the premises were transferred to the trusteeship of BRLSI Trustees. A newsletter and a programme of lectures was started, the meetings being held in the nearby premises of the Bath and County Club.

1994 The nine Interim Trustees were formed into a Board to superintend activities and exercise the trusteeship. A lease of a large part of the premises for 7 years to Bath Training Services at a reduced rent in return for their refurbishment by the Bath City Council was negotiated in August. A Development Officer was appointed. Discussion Groups were formed.

Refurbishment of the premises began, together with work on a development plan and on a policy for the collections. A Board of Trustees consisting, according to the Articles of Association, dated 27 September 1993, of 11 appointed and 5 elected Trustees was formed on 29 September 1994.

1995 In March, refurbishment being complete, the Institution occupied the part of the premises available to it. Subscriptions were set at £15 per annum for individual Members, £20 for a couple, £5 for a student, £50 for a benefactor and £500 for a Life Member. The programme grew to 70 events a year. The first Annual General Meeting of the Institution was held on 11 October.

1996 After occupying its part of the premises for a year, the balance of the Institution’s policy was changed towards developing the Institution through its Members’ programme of meetings while continuing, as funds allowed, the conservation and cataloguing of the collections with the aim of their use for research and in a virtual museum accessible worldwide on the Internet. The full-time Development Manager resigned and she was replaced by a part-time Curator and a part-time Administrator. Increased numbers of volunteers worked on the collections and archives.

1997 The number of discussion groups, generally holding meetings once a month, grew to eight and the Institution continued its drive to build a reputation as a cultural institution, to develop the membership and to maintain a sound if restricted financial base. To that end, rental income was doubled by letting the Moore Room.

Two sponsored exhibitions were mounted and under Paul Elkin, the Curator, a steady team of volunteers worked on the collections, library and archives, while other volunteers organised events, supported the Administrator and contributed to the running of the Institution in a number of ways, thus helping to keep costs within income. The first annual report of the revived Institution was published and the Institution’s Internet Website was established.

1998 The Institution’s programme continued to prosper, with well-attended events of high quality, a day conference, two exhibitions, a public meeting chaired by the Member of Parliament for Bath to discuss a scheme to develop part of the city, and meetings by four kindred Bath societies held on the premises as well as joint meetings with five national scientific and cultural institutes and societies.

Members themselves led nearly half of the Institution’s events in subjects in which they were expert or practised. A Strategy Group was formed to consider the longer term future of the Institution.

1999 The Proceedings of the Institution for 1998 were published as an annual volume for the first time in place of the previous four-monthly issues. Activities developed with increasing numbers of day conferences, series of lectures on particular themes, and a foreign visit as well as a debate on aspects of the European Union. The programme extended to about 120 events during the year and the Chistmas Lecture by a distinguished scientist was instituted.

2000 Lunch-time meetings were instituted in response to some reluctance by many Members to come out to attend evening meetings. The number of Trustees elected by Members was increased from six to eight in view of the leading part taken by Members in running the Institution and the Board of Trustees established regulations for the Institution. Voluntary effort towards running the Institution grew to the equivalent of at least 5 full-time staff.

2001 The Millennium Year saw the number of events rise to a total of 237, counting 99 held in the Institution by outside bodies. The conveners of the discussion groups were reconstituted to form the Programme Sub-committee and an Astronomy Group was started with the William Herschel Society of Bath. The Christmas lecture was given by the Astronomer Royal. The Membership rose to 467. Paul Elkin, the Curator, resigned upon moving to East Anglia. He had directed recovery work on the collections for five years with great effect.

2002 A new lease for three years from January 2002 was negotiated with the present tenants but at a full rent for educational use.

One of the founding fathers of chemistry, Joseph Priestley (1733-1804) stumbled across photosynthesis, is credited with the discovery of oxygen and accidentally brought us soda water. He was also a member of BRLSI’s predecessor, the Bath Philosophical Society.

Joseph Priestley (picture: Wikipedia)

2004 marked the two hundredth anniversary of the death of Joseph Priestley one of the most influential and colourful scientists of the eighteenth century. He had a Bath connection since he was a member of the Bath Philosophical Society, a forerunner of the BRLSI, when he lived and worked at Bowood House in Calne, Wiltshire. There he was the librarian and scientific guru for Lord Shelburne, the 1st Marquis of Lansdowne, and it was here that he first identified oxygen. It is for this discovery that he is best remembered today.

Priestley was born in Birstal Fieldhead near Leeds in 13th March 1733, the eldest son of a cloth-dresser. His mother died when he was seven years old and his aunt mainly brought him up. He was educated for the dissenting ministry and spent much of his life both as a teacher and a preacher. Priestley was a true polymath, writing books and articles on theology, history, education, aesthetics and politics as well as science. During his lifetime he was as well known for his views on theology and politics as for his work in science.

Priestley married Mary Wilkinson in 1762. She was the daughter of Isaac and sister to John and William Wilkinson. All three men were prominent iron masters in the eighteenth century.

His scientific interests began around the middle of the 1760s. It was during this time that he began to write his book History and Present State of Electricity. For this work he received the help from several people. These included Benjamin Franklin (The American academic, politician and scientist who was present at the signing of the American Declaration of Independence), William Watson (An apothecary who lived in Bath and was also a member of the Bath Philosophical Society; he was also a friend of William Herschel) and John Canton (Another scientist born in the West country at Stroud in Gloucester in whose honour the Institute of Physics recently erected a blue plaque on his schoolhouse in Stroud).

While writing the book he carried out several experiments. Among them was an ingenious demonstration of the inverse square law of electrostatics. This is generally known as Coulomb’s law but the work of Priestley in fact predates that of Coulomb by nearly twenty years. Mainly as a result of his work on electricity, he was elected to Fellowship of the Royal Society in 1766.

In part as a result of financial problems stemming from his increasing family responsibilities, Priestley resigned a teaching position that he had to become the minister of Mill-Hill Chapel, which was a major Presbyterian congregation in Leeds. It was here that he completed History and Present State of Electricity (1767) and also wrote the History of Optics (1772). While living and working in Leeds he became a founder member of the Leeds Library, becoming both its Secretary and later President. In 1989 the Leeds Library was prominent in setting up the Association of Independent Libraries, to which the BRLSI also belongs.

The Leeds Library holds important archival material on Priestley’s time there. It was while he was in Leeds that he began his most important scientific researches namely those connected with the nature and properties of gases. A bizarre consequence of this is that Priestley can claim to be the father of the soft drinks industry. He found a technique for dissolving carbon dioxide in water to produce a pleasant “fizzy” taste. Over a hundred years later Mr Bowler of Bath benefited from this when he formed his soft drinks industry.

Discovery of Oxygen

Priestley entered the service of the Earl of Shelburne in 1773 and it was while he was in this service that he discovered oxygen. In a classic series of experiments he used his 12inch “burning lens” to heat up mercuric oxide and observed that a most remarkable gas was emitted. In his paper published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1775 he refers to the gas as follows: “this air is of exalted nature…A candle burned in this air with an amazing strength of flame; and a bit of red hot wood crackled and burned with a prodigious rapidity, exhibiting an appearance something like that of iron glowing with a white heat, and throwing sparks in all directions. But to complete the proof of the superior quality of this air, I introduced a mouse into it; and in a quantity in which, had it been common air, it would have died in about a quarter of an hour; it lived at two different times, a whole hour, and was taken out quite vigorous.”

Although oxygen was his most important discovery, Priestley also described the isolation and identification of other gases such as ammonia, sulphur dioxide, nitrous oxide and nitrogen dioxide.

By 1780 the working relationship between Priestley and the Earl of Shelburne had cooled somewhat and he decided to move with his family to Birmingham, where he became preacher at the New Meeting House. This was one of the most liberal congregations in England. For Priestley his time at Birmingham was among the happiest in his life.

He soon became involved with the Lunar Society – a small group of academics, scientists and industrialists with wide ranging interests who were prominent in spearheading the Industrial Revolution in England. The Lunar Society was so named because its members met at full moon thereby facilitating travelling home in the dark after the meetings. Fellow members of the Lunar Society included Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles and also a pioneer in the theory of evolution), James Watt and Josiah Wedgwood.

Although Priestley played an active role in the Lunar Society his interests turned more and more towards theology. He became an active dissenter with outspoken criticism of the established church. These were dangerous times to be alive with the French Revolution (1789-91), which Priestley supported, sending shock waves around Europe. In 1791 on the second anniversary of the storming of the Bastille a “Church and King” mob in Birmingham destroyed the New Meeting House as well as Priestley’s house and laboratory. He barely escaped with his life and most of his equipment and records were lost. Priestley briefly joined a dissenting group in London at Hackney but after renewed vitriol against him and his family he emigrated to the United States of America in 1794.

He was warmly welcomed in America and offered the chair of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, which had been founded by Benjamin Franklin. Priestley declined and settled in Northumberland, Pennsylvania in an area intended for British émigrés fleeing political persecution. He was befriended by Thomas Jefferson, who became President of the United States in 1800. However, Priestley’s final years were sad and lonely; his favourite son died in 1795 and his wife a year later. He himself died on the 5th February 1804 aged seventy-one and is buried in Northumberland where his house has now been turned into a museum.

Priestley should be included in any pantheon of scientists. The bicentenary of his death is an opportune time to reassess his life and work and several events are planned during the year. He possessed enormous scientific skills and originality of thought as well as having the courage to promote unpopular views. He was a man of rare insight and talent.

Dr Peter J. Ford

Department of Physics, University of Bath

Jan. 2004

BRLSI can claim a unique connection to Charles Darwin through the work of his life long friend and fellow naturalist Rev. Leonard Jenyns (1800-1893). The two met at Cambridge and, when Jenyns declined the offer of the place of naturalist on board the Beagle owing to his clerical duties, he proposed the young Darwin as the ideal substitute..

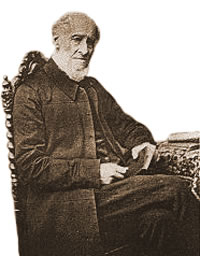

Rev. Leonard Jenyns

Jenyns’s earliest memories were of the funeral of Lord Nelson in 1806. His great uncle Leonard Chappelow gave him a copy of Nicholson’s Encyclopaedia when he was 10, which he later said was “the foundation stone of his whole library”. Two years later, aged 12, he wrote a letter announcing his decision to become a naturalist.

His father was a Canon of Ely Cathedral and his mother was daughter of the celebrated Dr. Heberden, Physician to the Royal Family, whose connections proved valuable to Jenyns later on. He was sent to school at Eton in 1813, where his first leanings to natural history were strengthened, and where he recalled writing 66 hexameters of verse on the occasion of the first British Arctic voyage in 1818.

He identified “an early fondness for order, method and precision”, which accurately describes his notebooks and neat hand, in items he left us. After Jenyns graduated from Cambridge in 1822, he was ordained priest in Christ’s College by the Master in 1824, and was appointed Curate and later Vicar at Swaffham Bulbeck, a parish of 700 people adjoining his father’s estate at Bottisham.

He collected insects when quite young and also formed a collection of birds’ eggs and British freshwater shells.

Learned Societies and publications

He was a member of a number of learned societies: Cambridge Philosophical Society (1822), Zoological Society (1826), British Association for the Advancement of Science (1832), Linnean Society (1832), Entomological Society (1834), Geological Society of London (1835), Ray Society (1844).

Important Works

Jenyns wrote many papers and books including Calendar of Periodic Phenomena in Natural History, Observations in Natural History (1846), Observations on Meteorology (1858), a Memoir of the Rev. John Stevens Henslow (1862), Professor of Botany at Cambridge, mentor of Darwin, and Jenyns’s brother-in-law, as well as Chapters in My Life (1887, 2nd ed. 1889). He was proud to be asked to edit a new edition of Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne in 1843, White being one of his heroes.

He thought that his two most important works were Manual of British Vertebrate Animals (1835) and his editing of the Fishes of the Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle (1840-42). In his memoirs he describes how he was offered the post of naturalist on board the Beagle’s famous round the world voyage but, after some thought, felt that his duty lay with his parish. Charles Darwin took his place and it was during this voyage that Darwin’s observations and thoughts on all he had seen during the voyage, led to his famous work which revolutionised the way the natural world was conceived.

Among Jenyns’ collections in the BRLSI are four volumes of correspondence with Darwin and other ‘Men of Science’. Altogether there are nearly 700 letters from more than 200 correspondents, stretching from 1817 until the 1870’s. These letters have been transcribed by Sheila Metcalf and Trudy Wallace and can be consulted at the BRLSI. The Jenyns correspondence is registered with the National Register of Archives.

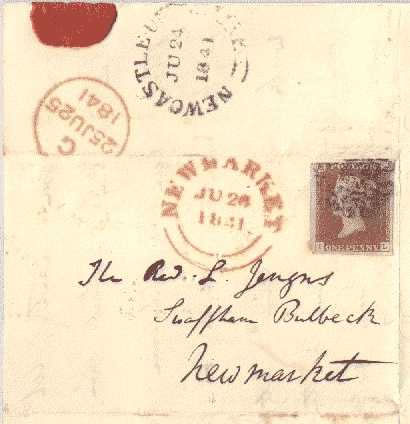

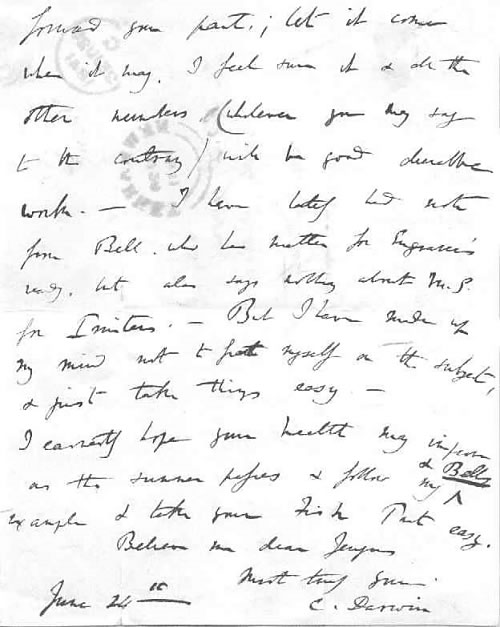

Example of Jenyns’ correspondence with Darwin

Dear Jenyns

I have been scandalously indolent in not sooner answering your kind enquiries about me and mine. The country at first acted like magic on me, but the charm has latterly lost some of its virtue. I am, however, a good deal stronger than when in London, but I do not feel that I shall have any mental energy for a long time and the Doctors tell me, it will be some years, before my constitution will recover itself.

You and I can tell people in health, they have little idea what an unspeakable advantage they possess over us poor weak wretches. I judge from your note that Hitcham acted on your health, somewhat like this place did on mine, that is as a temporary relief.

I can only repeat, what I have said before to beg you not to give yourself any anxiety to hurry forward your part; let it come when it may. I feel sure it and all the other numbers (whatever you may say to the contrary) will be good dudrable work. I have lately had note from Bell, who has matter for Engravers ready, but also says nothing about M.S. for Printers. But I have made up my mind not to fret myself on that subject and just take things easy.

I certainly hope your health may improve as the summer passes and follow my an Bell’s example and take your Fish Part easy.

Believe me dear Jenyns

Most truly yours

C. Darwin

June 24th

Below is a section from the original letter:

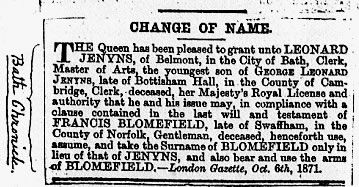

A change of identity

Leonard Jenyns changed his surname to ‘Blomefield’ at the age of 71, in order to comply with the terms of an inheritance. Although unusual today, this was apparently not uncommon in Victorian times. It was several years before Darwin got used to addressing letters using his new name. This illustration shows the announcement in the Bath Chronicle.

Jenyns the Naturalist

Jenyns in his Manual of British Vertebrate Animals says of the Rudd or Red-Eye: “12 to 14 inches, general appearance resembling that of the Roach, but the body deeper and thicker; the back more arched, and forming a slightly more salient angle at the commencement of the dorsal fin;…”

Jenyns served as Vicar of Swaffham Bulbeck near Cambridge, and married there in 1844. Owing to his wife’s poor health the couple moved to Bath in 1850, where they lived in South Stoke and Swainswick. When his wife died in 1860, Jenyns moved to Darlington Place, and later Belmont, marrying again in 1862.

He was founder in 1855, and long time President, of the Bath Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club, whose proceedings abound with his papers. He donated his library of more than 2,000 books, including numerous manuscripts, scrap books and his correspondence. Jenyns also left the Institution a large collection of shells and an impressive herbarium.

An interest in meteorological matters had begun early when he noticed Gilbert White’s comments about the link between animal behaviour and weather. From this he developed his own ideas and, much later, he read a paper on the subject to the Physical Section of the British Association at their annual meeting in Bath in 1864. The paper aroused considerable interest and he followed this by setting up a meteorological observatory in the Institution Gardens in 1865, which he monitored regularly, analysing and summarising the readings in 1875 and 1885.

Surprisingly with his chosen subjects, Jenyns felt he could not draw (unlike the rest of his family) and he always preferred not to attempt to study two subjects at once. In his early years, he expressed a disdain for four things that might so easily have been part of the lot of a rural vicar: “Sporting, Farming, Politics and Magisterial Business” and his focus and studying instincts were confirmed by one of his servants who noted “My master, you know, is such a thinking gentleman”. Towards the close of his career he was held in honour as the patriarch of natural history studies in Great Britain.

Leonard Jenyns is commemorated today at BRLSI in the name of the Jenyns Room, the Institution’s main gallery space, which is used for art and museum exhibitions.

3rd Marquis of Lansdowne

Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, Marquis of Lansdowne, K.G. Engraved by F.J.Smith after a Daguerreotype by Kilburn in 1852, for the “Illustrated London News”

Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquis of Lansdowne, K.G. (1780-1863), was the only son of the 1st Marquis of Lansdowne (2nd Earl of Shelburne) by his second marriage. He succeeded his elder half-brother to the title in 1809. One of the most notable of Whigs of the first half of the 19th century, he was a champion of catholic emancipation, the abolition of the slave-trade and the cause of popular education.

He served in Canning’s cabinet as Secretary of State for Home Affairs in 1828 and was Lord President of the Council both under Gray and Melbourne and during the whole of Lord John Russell’s Ministry.

His position was one of great power but he exercised consistent moderation. He and his refined wife Louisa made their home in Wiltshire, Bowood House, a magnet for society. He was patron of arts, and the local poets Thomas Moore (1779-1852), George Crabbe (1754-1832) and William Lisle Bowles (1762-1850) were frequent guests at his social gatherings, mingling with statesmen, scientists and other writers.

He had many connections with France and it is significant that the well known writer Mme de Stael visited Bowood House and Bath in 1813. His great interest in the arts and sciences made him the perfect choice as the first President of Bath Literary and Scientific Institution (BRLSI).

Trudy Wallace 2002

The poet Thomas Moore

Bust of Thomas Moore in the BRLSI collection

The poet Thomas Moore (1779-1852) was born in Dublin but lived in Sloperton, near Bowood House, where he was a frequent visitor at the social gatherings of his patron, the Marquis of Lansdowne.

Together with the Marquis of Lansdowne and the Wiltshire poets Crabbe and Bowles, he was present at the grand opening of the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution in January 1825. From his diaries we get a flavour of this evening:

The grand opening today of the Literary Institution in Bath. Attended the inaugural lecture by Sir G. Gibbs, at two. Walked about a little afterwards – and to dinner at six. Lord Lansdowne was in the chair […] “Lord L. alluded to us in his first speech, as among the literary ornaments, if not of Bath itself of its precinct […].

Thomas Moore then himself gave a speech, received by “a burst of enthusiasm” by his audience in which he talked of the “springs of health with which nature had gift the fair city of Bath”.

Thomas Moore and his wife Bessie were frequent visitors to the city, as their beloved daughter Anastasia went to school here. His poetry was loved by his contemporaries, especially his Irish Melodies, Lalla Rookh and the Loves of the Angels. In Prose he wrote the Life of Sheridan and as a friend of Lord Byron, he published The Letters and Journals of Lord Byron and in 1830 edited Byron’s collected works.

He was a frequent guest in aristocratic circles at Lacock Abbey and Bowood, dining, dancing, singing, reciting poetry and talking about politics.This was witnessed by an astonished 6th Duke of Devonshire, visiting Bowood in April 1826, who wrote in his diary that Thomas Moore, “the little urchin” was shown straight into Lord Lansdowne’s room without any ceremony.

The Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution is fortunate in having in its collection a bust of the poet Thomas Moore.

Trudy Wallace 2002

Philip Bury Duncan

John Shute Duncan

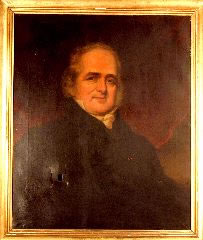

John Shute Duncan (1768-1844, left) and Philip Bury Duncan (1772-1863).

The two Duncan brothers were very important to the BRLSI. In 1824 and 1825, they feature very prominently in the minutes of the Committee meetings which record the foundation of the Institution. They helped greatly, administratively and creatively in setting up the Institution: as Chairmen of meetings and as committee members concerned with management of the museum and with collecting and arranging antiquities

They were also generous donors of casts from Florence, books and many natural history items. Philip Bury Duncan was elected Chairman of the BRLSI in 1834 to 1859 and in 1841 he also became President of Bath United Hospital. His essays on a variety of subjects were published in Oxford in 1840 and show the extent of his knowledge on sculpture and Roman antiquities, on Zoology, Geology and foreign travel.

To be part of the BRLSI was only a sideline for the brothers They had houses in Bath but their work was principally in Oxford, as keepers of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. John Shute Duncan, who had a career at the bar and a fellowship in New College, became keeper of the Ashmolean in 1823 for six years. His younger brother followed in his footsteps and took over as keeper from 1829-54.

This painting by of P.B. Duncan was commissioned from Mr. Phillips, R.A. by members of the Institution in 1837 to celebrate his long-term Chairmanship, his many generous donations, and his provision of funds to refurnish the library.

Through this continuity they achieved a miraculous transformation of a museum they had found in a neglected state. They set up governing principles, started a radical reorganization programme and prepared a 51 page “Introduction to the Catalogue of the Ashmolean Museum”. This first catalogue, published in 1836, shows how the Duncans had transformed and extended the old collection, especially in natural history, and attracted many new donors.

This approach must have been part of their strategy in Bath, as many substantial donations took place during their time at the Institution. In 1854 the 82 year old P.B. Duncan resigned his keepership after a long and fruitful career at the Ashmolean. He died in his house at Weston near Bath, age 91, in 1863. As the Duncan brothers had an important influence on the BRLSI the Duncan Memorial Fund was set up in 1867 to help the improvement of the library and the museum. Information from Jerom Murch “Biographical Sketches of Bath Celebrities”, (London 1893) and archival material from the BRLSI.

The double portrait of John Shute Duncan and Philip Bury Duncan shown above was a copy of the paintings in the Oxford Ashmolean Museum, by the artists T. Kirkby and W. Smith. It was given to the BRLSI in 1867 by the daughter of J.S. Duncan, Mrs. Fraser from Manchester, and hung above a brass plate in the vestibule of the BRLSI in Terrace Walk. Dedicated to the brothers, this plate celebrated their long and fruitful association with the Institution.

Trudy Wallace 2002