West Africa and Britain through one man’s collection

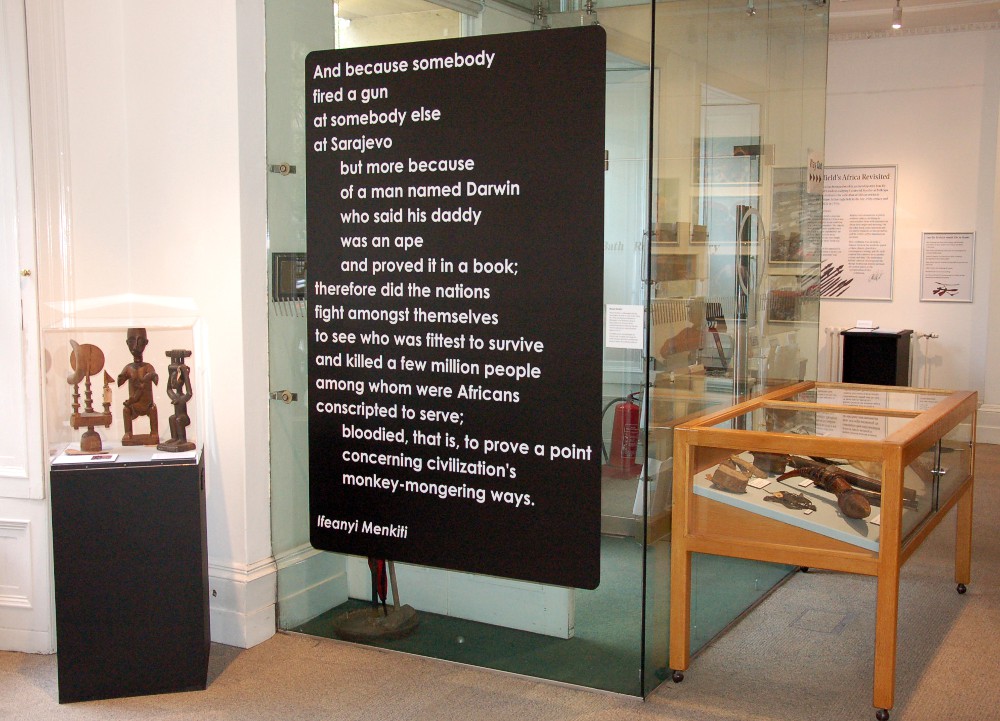

Inglefield’s Africa Revisited was a 2014 exhibition produced in partnership with Jana De Brabant, an MA student studying Curatorial Practice at Bath Spa University. It re-evaluated a collection of African artefacts collected by Major Arthur Inglefield in the late 19th century and donated to BRLSI in 1936. Jana De Brabant focussed upon the motivations of colonial collecting and changes to museum display methods and narrative approach since then. Museum interpretation changes with societal trends and it may be that an exhibition produced in the 2020s would be quite different again.

Curator’s statement:

After Major Inglefield donated this collection to us, it was arranged for display in the tradition of a cabinet of curiosities. The objects were grouped closely together on a shelf and were not explained to the viewer. There was little or no interpretation and one was simply intended to enjoy their ‘exoticism’ and ‘otherness’.

I would argue that this approach is not acceptable in today’s society, yet there are still art museums that display cultural material as purely aesthetic objects, declining to contextualise them with information about their origin and meaning. On the other hand, some museums put too much emphasis on interpretation and the visitor suffers information overload.

This exhibition tries to strike a balance between the aesthetic appeal of these objects, placed in a contemporary setting, and the vital context that connects us to another culture and time. The motivation behind colonial collecting and the change in museum display methods are central points to the interpretation of this exhibition.

Victorian Collecting: the Empire brought home

During the so called ‘Scramble for Africa’, initiated by the Berlin Conference, Britain received a substantial amount of territory on the African continent. The Asante kingdom (today’s Ghana) and Nigeria were from then on part of the British colonies. Collecting was seen as the primary way to gain knowledge about the foreign peoples during the colonial era.

Decorated horn

Little is known about this beautifully decorated horn from Nigeria. It is probable that it was used as a container and carried by a strap on the shoulder.

Drums

Drums play a very important part in many African societies. Those displayed here were all made by the Asante people. They serve as musical instruments and as a means of communication. Via intricate combinations of rhythm and sound, villages could contact each other and send messages during war and on other occasions. They continue to have a strong cultural importance today.

The drum that is decorated with the jaw bones and skull is most likely a ceremonial drum that was used for special occasions only. The skull and bones are fastened with wire, which may indicate that they are not the originals. Whether Inglefield or somebody else replaced or simply added this feature to the drum is unclear. It is also unclear whose remains are attached.

Museums were founded and expanded all over Europe and filled with objects brought back from the colonies. Displays of the ‘exotic’ and the ‘curious’ were popular forms of entertainment during Victorian times. ‘Us’ and ‘our’ civilisation compared to the ‘others’ and their ‘underdeveloped’ way of life was the underlying message in many museums’ ethnographic exhibitions. This helped to unify opinion about Britain and its involvement in Africa.

Collecting and displaying exotic and curious objects in one’s home was seen as a way to show off wealth and to gain and uphold prestige. Inglefield was not very successful in continuing his family’s military career and he might not have been particularly selective about what he collected or inherited from his grandfather, but it seems he never questioned the need to collect.

Major Inglefield

The objects on display were collected by Major Arthur Augustus Hamlet Inglefield, born in 1855 in Southsea, Portsmouth. Inglefield travelled to West Africa at least twice between 1890 and 1894, though his reasons for doing so are unclear. On one travel record his occupation is stated as ‘agent’, a term used at that time for government representatives who arranged “treaties of protection” with provincial rulers.

These treaties were a common tool for colonisation in the decades following the Berlin Conference of 1884–5. Living in the colonies in those days was considered dangerous and unpleasant; successful, wealthy people preferred to stay in their home countries. On his return from Africa, Inglefield married Ethel Flora Elizabeth Brammall-Wall.

Inglefield was from a military family and served in the army for much of his life, first signing up as a Lieutenant at the age of 17. However, he failed to rise above that rank and resigned his commission in the year of his marriage. Following bankruptcy in 1914, he was readmitted to the army and temporarily made Captain during the First World War. It is unknown why he is commonly referred to as Major, as he never attained that rank; indeed he was not a very successful officer. In 1918 he reluctantly resigned his commission, having been pressed into retirement by his dissatisfied superiors.

Inglefield died in 1935, having been a resident of Bath for ten years. Ethel Inglefield, his widow, donated his collection to the BRLSI in 1936.

Nigerian hats

Made from woven and dyed grass

Brass container

Brass container with fine-lined decorations, probably used for containing shea butter. Shea butter is produced by roasting the shea nut which are then ground and mixed with water until a paste forms. The oils separate from the rest of the paste and make a smooth butter that can be used as a lotion on the skin.

The Collection

West African objects make up the majority of Major Inglefield’s collection, though it also includes material from other parts of the world such as South Africa and the Pacific region.

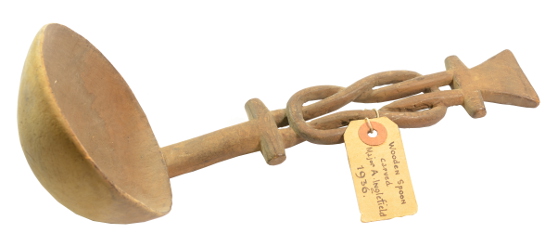

Spoons

These spoons are carved by the Asante, Ghana. The one on the left has a round end which is used for pounding grain. The other one has a handle shaped like a wisdom knot, the so called nyansapo, which symbolises patience and intelligence. This spoon probably belonged to a person of status.

Arthur’s great grandfather, John Nicholson Inglefield, was in command of two vessels patrolling the coast of West Africa from 1788 to 1792, and he may have passed down objects obtained at that time. It is also probable that the younger Inglefield inherited some of his non-African objects from his grandfather, Rear-Admiral Samuel Hood Inglefield, who served in South America and who rose to the office of Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies and China Station.

Swords

Left side: Asante, Ghana. Curved blade with leather sheath

Right side: Senegalese dagger and leather sheath.

Most of the objects shown in this exhibition are from what we now call Nigeria and Ghana. West African peoples are renowned for their exquisite carvings, sculpture, and masks, but interestingly Inglefield’s collection holds hardly any such items. He acquired many objects which could be considered as tourist souvenirs and it is doubtful that he searched for particular items, as a systematic collector would have done. It appears he chose objects that appealed to his personal taste; certainly the collection reflects his military interests and includes a large number of knives, spears, and other weaponry.

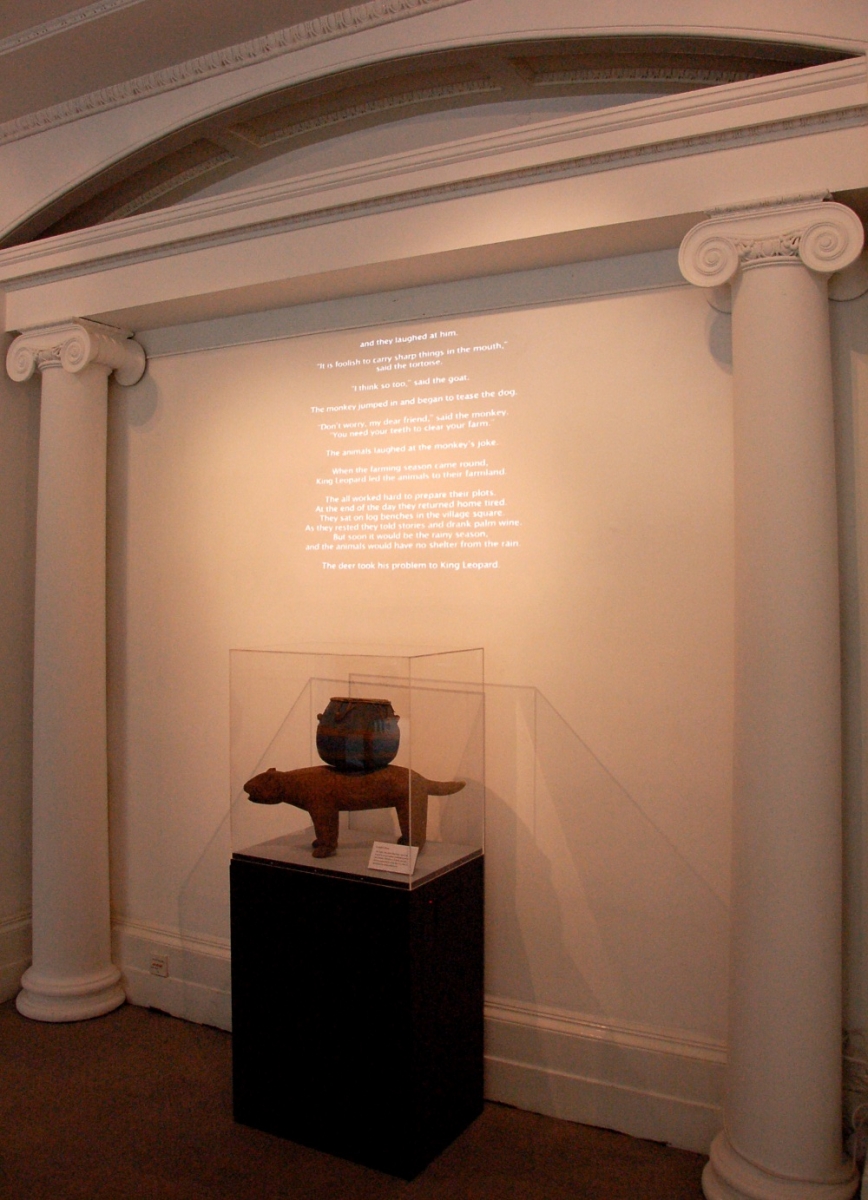

Wooden carvings

Woman holding a mancala board and a woman holding an infant. Probably made for sale to tourists.

Mancala is a board game that originated on the African continent and is now played all over the world. The Asante played a version called nam-nam or oware which was seen as the national game.

The Asante

The Asante (or Ashanti) kingdom was one of the biggest and most successful in West Africa. The first Asantehene (king), Osei Tutu, united the Asante chiefdoms in 1670, establishing an Empire. Britain gained part of their territory in 1874 and the British Gold Coast was established shortly after that.

Stool

This stool was carved from a single piece of wood by the Asante in Ghana. Such stools have a strong spiritual significance for the Asante. According to legend, a golden stool, the so-called Sika Dwa Kofi, was passed down from the sky to the first King of the Asante, Osei Tutu, as a symbol of the newly united nation and its power. An early British traveller compared it to the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey.

This example does not represent the traditional style of the original Asante stool and was probably fashioned for the tourist trade; the figure holding the seat would have appealed to Western aesthetics.

The Asante gained their wealth and success through trading in gold and slaves in the coastal region occupied by the Fante people. Since the 17th century, Europe has traded with the people on the African coastlines. In West Africa, the Portuguese were the first to establish a steady trade in gold and slaves with the inhabitants. They were replaced, first by the Dutch and later the British, who took over the pre-established coastal forts. The British eventually demanded control over the gold trade and they came into conflict with the Asante, with whom they fought several battles. The Asante were eventually defeated in 1874, when the capital Kumasi was destroyed. The Asante people continued to resist British rule however, and an established colony was not possible until 1902. After Ghana’s independence in 1957, the Asante used their history to unify their people as a kingdom once more, which still exists within modern Ghana. The Asantehene still reigns today, but holds a more symbolic and representational role for the Asante culture.

The Asante are renowned for their exquisite gold craft. Gold is intricately linked with the king and his court and is just as important to the culture today as it was when it was founded.

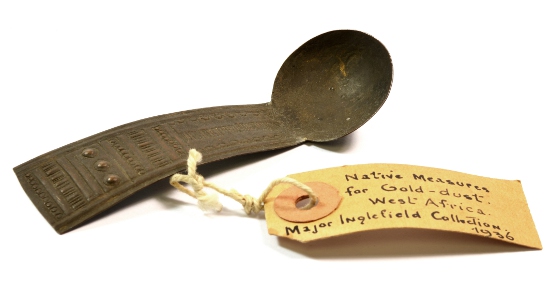

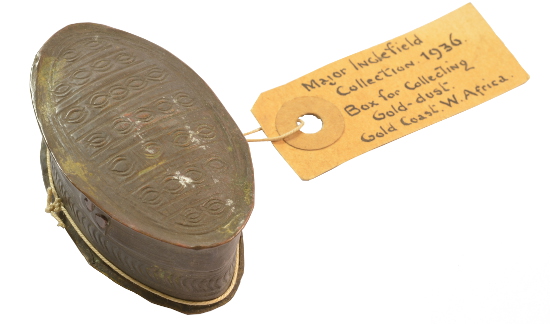

These are three brass objects used by the Asante for working with gold dust.

The spoons are used to measure gold dust, the bigger spoon has a funnel at one end which can be used to blow out impurities. The box is used to store the dust. Asante, Ghana.

Umbrella ornaments

These objects are part of the large umbrellas used in Asante cultural festivities. The wooden stand holds three carved symbols, the so called ntuatire that would be attached to the central hub of the umbrella. They probably would have been gilded originally. Asante umbrellas are part of the costume of these events; along with the colourful fabric that is worn by important Asante representatives, the umbrellas are there to impress their guests as well as to provide shade during ceremonies.

Fly whisk

Made of horse hair. High officials have someone standing by to keep flies away.

Other ethnic groups

While Ingelfield collected mainly from the Asante, West Africa is a culturally diverse region. Other ethnicities represented in his collection are the Yoruba from Nigeria, the Fante from Ghana, and Senegalese material that has yet to be attributed to a specific group. It is not clear why Inglefield’s collection has this bias; it may simply be that he travelled mainly in the Asante kingdom.

The Fante

The Fante are from the south of Ghana. Their kingdom provided a barrier between the first settlements of the British on the coast and the Asante kingdom further inland. The Fante were defeated by the Asante in a war at the beginning of the 19th century. The British intervened, establishing a protectorate over the southern region, which would become the Gold Coast in 1873.

Leopard drum

The Fante, who made this drum, regard the leopard as a royal animal, symbolising power and wisdom. Therefore, it is likely that this drum is connected to ceremonies of a chief or a king of the Fante community.

The Yoruba

Yorubaland occupies the West of Nigeria, although the Yoruba also have substantial communities in Benin, Togo, and Ghana. The fine carvings and naturalistic style of the Yoruba are well represented in museums worldwide. In 1914 the British officially established the colony of Nigeria. Before that time Yorubaland was made up of various semi-autonomous states united through a king in the ancient city of Ife.

Fertility carving

This carved amulet is made by the Yoruba and would be carried in a woman’s belt. It is used as a charm to ensure fertility and healthy children.

The Asante also carried fertility charms with them for the same reasons. This carving is called akua’ba and is carried on the back by women.

Bronze figures

Made by the Yoruba, these figurines depict women holding daily utensils such as pots and baskets and men holding flintlock muskets.

What use they might have had in Yoruba culture is unclear and it is probable that they were fabricated for the early tourist trade.

The Hausa

Sword

Powder flask

Leather powder flask made to store gun-powder. Hausa, Ghana.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]