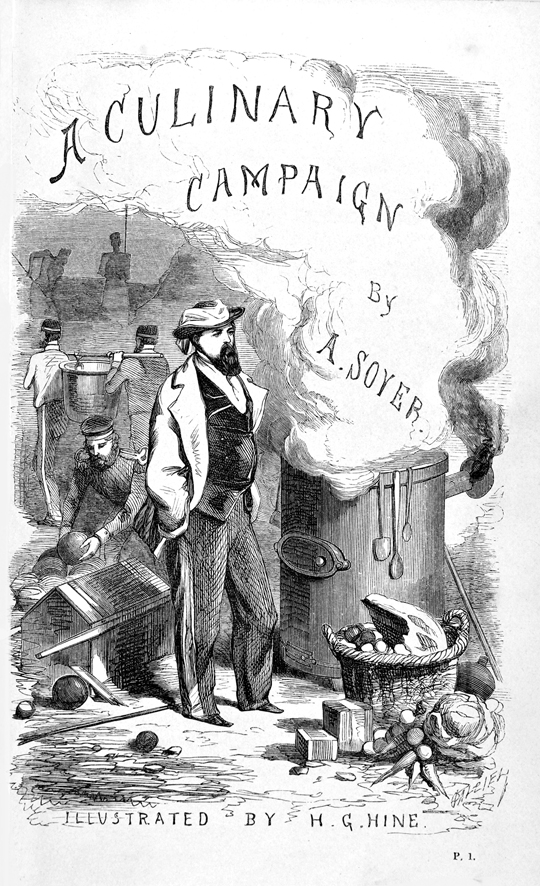

That odd metaphor, the ‘theatre of war’, provokes an image of battlefield arena and attendant cast. The Crimean War certainly had its own ‘celebrities’: Florence Nightingale; Mary Seacole, the Jamaican nurse; the infamous Lord Raglan, Commander of the British Troops. Another, less known, was Alexis Soyer, chef at the Reform Club, inventor, a generous eccentric with a social conscience and a flair for self-publicity, who travelled to the Crimea on a mission to improve the diet of the soldiers, chronicled in his narrative ‘Soyer’s Culinary Campaign’ (published 1857).

A Crimean Adventure

Soyer became involved in the war at a time when the health of the British soldiers in the Crimean Peninsula during the harsh winter of 1854 had deteriorated to such an extent that only 9000 men out of 32,000 were considered in fighting condition, depleted by cholera, dysentery and poor diet. Lord Raglan was chiefly blamed, for his battlefield strategies, but shortages of food and clothing supplied from England made matters worse. Morale was low: a letter in the Times, signed merely ‘A Crimean’, pleaded for ‘one public character who has it in his power to do us a really good turn…by publishing in the Times a receipt (recipe)… of how to concoct into palatable shape the eternal ration of pork and biscuit… Monsieur Soyer is the man’.

Not only was Soyer a society chef but he had form as a social reformer, thanks to the pioneering soup kitchens (serving a thousand portions an hour) he organised during the Irish Famine. He took up the challenge with characteristic energy and within a few days, using his social contacts to get him to the man at the top – Lord Panmure, the Minister of War – had arranged his departure for the Crimea. Panmure, who ended up taking much of the blame for the disastrous course of the war, blithely exhorted him to… ‘go to the Crimea and cheer up those brave fellows in the camp – see what you can do! Your joyful countenance will do them good Soyer; try to teach them to make the best of their rations’.

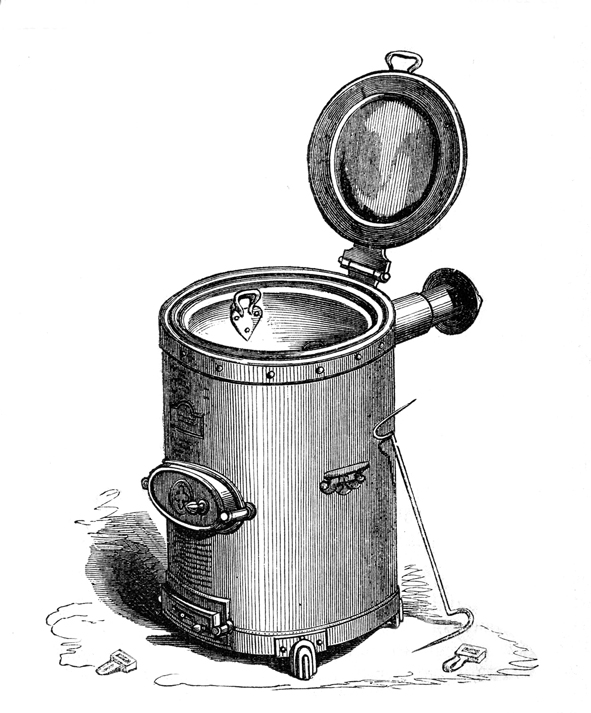

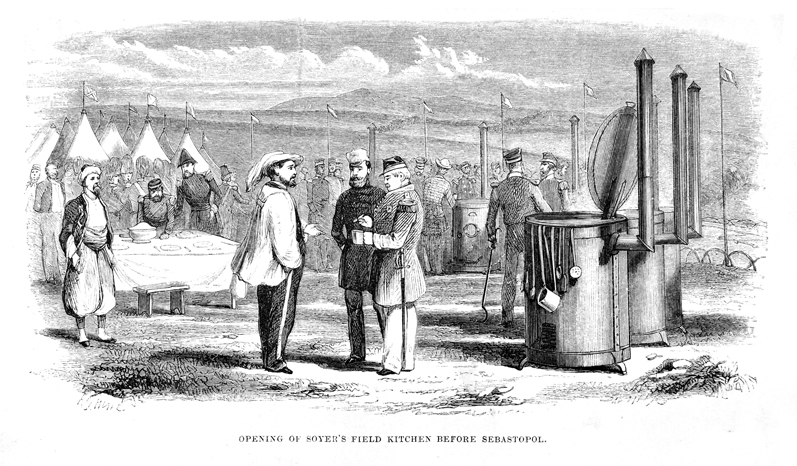

Soyer’s mind was focused on the deficiencies of both the diet of the troops and the army cooking equipment. His account of how he came up with an improved design of portable stove has all the breathless drama of a Victorian detective novel… ‘In a very short time I hit upon an idea which I thought could be easily carried out, and would answer perfectly. Losing no time, I jumped into a cab and immediately drove to the eminent gas engineers and stove makers, Messrs Smith and Phillips of Snow-hill. On submitting my plan to those scientific gentlemen, they pronounced it practicable and promised me a model, one inch to the foot, to be ready in a day or two.’ Not only would this new design of stove save fuel (he estimated 90 tons of wood per day), but it would reduce fumes and provide a source of warmth in the tents. At the end of his book he is already resolving ‘…upon my return to England to bring them out at as cheap a rate as possible for the use of small or large families. ‘“War” I said to myself, “is the evil genius of a time, but good food for all is a daily and paramount necessity”’.

Kitchen Nightmares

Having traveled to the Bosporus, Soyer paused in Scutari, some 300 miles from the battlefield, to wait for the delivery of his stoves and to begin his reforming work. Here Florence Nightingale was working hard to improve conditions for nursing the wounded in the two hospitals. Soyer became her avid admirer (arranging for the carriage she used to be shipped back to England at the end of the war, an act of homage), and she seems to have respected his professionalism, giving him a free hand to upgrade the kitchens in her hospitals, introduce better methods of sourcing provisions and transform the daily regime with nutritious and tasty meals.

Soyer found the kitchens full of fumes, run by orderlies with no knowledge of cooking. The food was often burnt or undercooked; meat was cooked by tying it to a piece of wood and dunking it in a large boiler where it cooked so fast the inside remained raw. It was then served without seasoning. He ordered cakes of dried vegetables from a Parisian supplier ‘consisting of carrots, turnips, parsnips, onions, cabbage, celery, leeks, thyme, savory, bayleaf, pepper and cloves…’ He arranged a blind tasting in the kitchen, with his own recipes side by side with the existing ones, of ‘beef tea, chicken broth, mutton broth, beef soup, rice water, barley water, arrowroot water, ditto with wine, sago with port, calves foot jelly etc. Everything was found superior and so highly commended by the doctor-in-chief.’

Soyer also cast a cool chef’s eye on the issue of waste…

‘When all the dinners had been served out, I perceived a large copper half full of rich broth with abut three inches of fat upon it. I inquired what they did with this.

“Throw it away, sir.”

Throw it away?” we all exclaimed.

“Yes sir, it’s the water in which the fresh beef tea has been cooked.”

Do you call that water?. I call it strong broth. Why don’t you make soup f it?”

“We orderlies don’t like soup.”

I took a ladle and removed a large basinful of beautiful fat which, when cold, was better for cooking purposes than the rank butter procured from Constantinople’.

Painful Scenes

In the company of Florence Nightingale, Soyer departed for the Crimea, to continue his programme of reform in the camp kitchens around the besieged city of Sevastopol. He describes their arrival at Balaclava, on the south side of the peninsula, fighting their way through ‘a dense crowd of Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Maltese etc, hundreds of mules, horses, donkeys, artillery wagons, cannon, shot and shell, oxen and horses kicking each other, waggons upset in deep mud-holes, infantry and cavalry passing and repassing. The road was execrable… We galloped to the top of a high hill (from whence) we could plainly distinguish everything for five miles around us. The camps, with their myriads of white tents, appeared like large beds of mushrooms growing at random. The sound of the trumpets, the beating of the drums, the roar of cannon from Sebastopol, made a fearful noise, whilst military manoeuvres and sentries placed in every direction, gave a most martial aspect to the landscape, backed by the bold and rugged range of mountains by which Balaklava is surrounded.’

The awful injuries inflicted by the Russians in the besieged city of Sevastopol are vividly described, along with the unreal corrective to suffering: ‘I witnessed the most painful scenes and numerous amputations….Wonderful was the kindness and celerity with which the doctors performed the operations. These were so numerous that before night several buckets were filled with the limbs… Having done all that was required at the hospital I returned to the camp, where an invitation awaited me to dine at the Carlton Club…The painful scenes I had witnessed weighed heavily upon the heart and mind, and a little relaxation was necessary.’

On his travels around the camps he met the kind-hearted Mary Seacole who was running ‘The British Hotel’, not far from the battlefield, a combination of canteen and London club, an enterprise which financed her unofficial nursing endeavours. She greeted him as an old friend, ‘God bless me, my son, are you Monsieur Soyer of whom I heard so much in Jamaica? I have sold many and many a score of your Relish and other sauces – God knows how many.’ They shared a bottle of champagne. Later Soyer set up a bakery to ensure a fresh supply of bread, previously shipped over in an uneatable condition from Constantinople. He trained the camp orderlies to cook better meals and organised an opening feast of ‘stewed fresh beef, Scotch hodge podge of mutton, salt pork and beef with dumplings’.

Victory Feast

Despite succumbing to Crimean Fever, Soyer survived to witness the end of hostilities in mid 1856. He described the bizarrely contrasted nature of army routine once the fighting was over. ‘… the camp bore the appearance of a monster banqueting hall. We have done fighting, said every one, so let us terminate the campaign by feasting, lay down our victorious but murderous weapons and pick up those more useful and restorative arms – the knife and fork’. As a celebrity chef, he was much in demand for these celebratory banquets, serving Filet de Turbot Clouté à la Balaklava and Bombe Glacé à la Sebastopol to the recent enemy, the Russian Commander, General Lüders.

Soyer returned to England but was dead within two years, his health weakened by his efforts. The Soyer Stove, however, remained in use by the Army for another hundred years and joined the Balaclava Helmet, the Cardigan and the Raglan sleeve as a lasting legacy of the Crimean War.

Article by Jude Harris (BRLSI Member)