BRLSI can claim a unique connection to Charles Darwin through the work of his life long friend and fellow naturalist Rev. Leonard Jenyns (1800-1893). The two met at Cambridge and, when Jenyns declined the offer of the place of naturalist on board the Beagle owing to his clerical duties, he proposed the young Darwin as the ideal substitute..

Rev. Leonard Jenyns

Jenyns’s earliest memories were of the funeral of Lord Nelson in 1806. His great uncle Leonard Chappelow gave him a copy of Nicholson’s Encyclopaedia when he was 10, which he later said was “the foundation stone of his whole library”. Two years later, aged 12, he wrote a letter announcing his decision to become a naturalist.

His father was a Canon of Ely Cathedral and his mother was daughter of the celebrated Dr. Heberden, Physician to the Royal Family, whose connections proved valuable to Jenyns later on. He was sent to school at Eton in 1813, where his first leanings to natural history were strengthened, and where he recalled writing 66 hexameters of verse on the occasion of the first British Arctic voyage in 1818.

He identified “an early fondness for order, method and precision”, which accurately describes his notebooks and neat hand, in items he left us. After Jenyns graduated from Cambridge in 1822, he was ordained priest in Christ’s College by the Master in 1824, and was appointed Curate and later Vicar at Swaffham Bulbeck, a parish of 700 people adjoining his father’s estate at Bottisham.

He collected insects when quite young and also formed a collection of birds’ eggs and British freshwater shells.

Learned Societies and publications

He was a member of a number of learned societies: Cambridge Philosophical Society (1822), Zoological Society (1826), British Association for the Advancement of Science (1832), Linnean Society (1832), Entomological Society (1834), Geological Society of London (1835), Ray Society (1844).

Important Works

Jenyns wrote many papers and books including Calendar of Periodic Phenomena in Natural History, Observations in Natural History (1846), Observations on Meteorology (1858), a Memoir of the Rev. John Stevens Henslow (1862), Professor of Botany at Cambridge, mentor of Darwin, and Jenyns’s brother-in-law, as well as Chapters in My Life (1887, 2nd ed. 1889). He was proud to be asked to edit a new edition of Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne in 1843, White being one of his heroes.

He thought that his two most important works were Manual of British Vertebrate Animals (1835) and his editing of the Fishes of the Zoology of the Voyage of the Beagle (1840-42). In his memoirs he describes how he was offered the post of naturalist on board the Beagle’s famous round the world voyage but, after some thought, felt that his duty lay with his parish. Charles Darwin took his place and it was during this voyage that Darwin’s observations and thoughts on all he had seen during the voyage, led to his famous work which revolutionised the way the natural world was conceived.

Among Jenyns’ collections in the BRLSI are four volumes of correspondence with Darwin and other ‘Men of Science’. Altogether there are nearly 700 letters from more than 200 correspondents, stretching from 1817 until the 1870’s. These letters have been transcribed by Sheila Metcalf and Trudy Wallace and can be consulted at the BRLSI. The Jenyns correspondence is registered with the National Register of Archives.

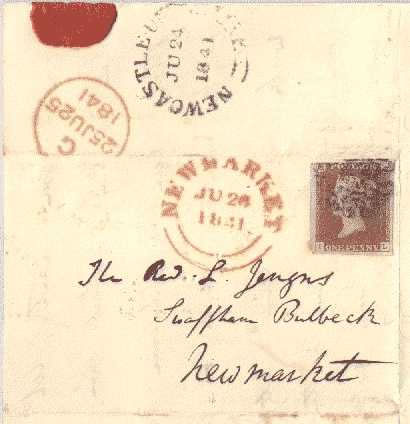

Example of Jenyns’ correspondence with Darwin

Dear Jenyns

I have been scandalously indolent in not sooner answering your kind enquiries about me and mine. The country at first acted like magic on me, but the charm has latterly lost some of its virtue. I am, however, a good deal stronger than when in London, but I do not feel that I shall have any mental energy for a long time and the Doctors tell me, it will be some years, before my constitution will recover itself.

You and I can tell people in health, they have little idea what an unspeakable advantage they possess over us poor weak wretches. I judge from your note that Hitcham acted on your health, somewhat like this place did on mine, that is as a temporary relief.

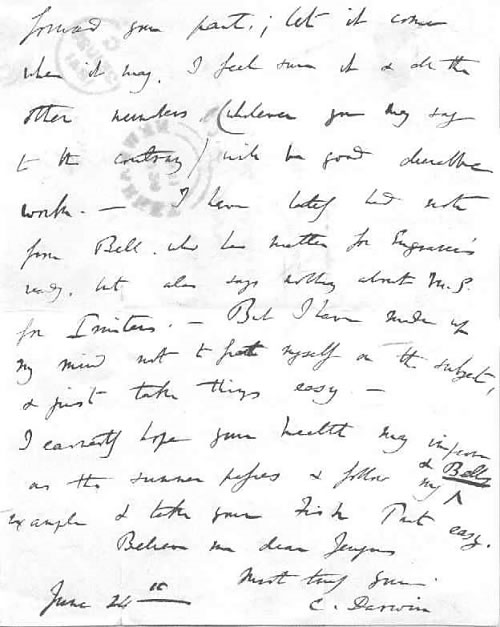

I can only repeat, what I have said before to beg you not to give yourself any anxiety to hurry forward your part; let it come when it may. I feel sure it and all the other numbers (whatever you may say to the contrary) will be good dudrable work. I have lately had note from Bell, who has matter for Engravers ready, but also says nothing about M.S. for Printers. But I have made up my mind not to fret myself on that subject and just take things easy.

I certainly hope your health may improve as the summer passes and follow my an Bell’s example and take your Fish Part easy.

Believe me dear Jenyns

Most truly yours

C. Darwin

June 24th

Below is a section from the original letter:

A change of identity

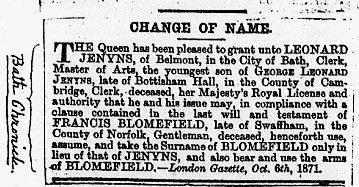

Leonard Jenyns changed his surname to ‘Blomefield’ at the age of 71, in order to comply with the terms of an inheritance. Although unusual today, this was apparently not uncommon in Victorian times. It was several years before Darwin got used to addressing letters using his new name. This illustration shows the announcement in the Bath Chronicle.

Jenyns the Naturalist

Jenyns in his Manual of British Vertebrate Animals says of the Rudd or Red-Eye: “12 to 14 inches, general appearance resembling that of the Roach, but the body deeper and thicker; the back more arched, and forming a slightly more salient angle at the commencement of the dorsal fin;…”

Jenyns served as Vicar of Swaffham Bulbeck near Cambridge, and married there in 1844. Owing to his wife’s poor health the couple moved to Bath in 1850, where they lived in South Stoke and Swainswick. When his wife died in 1860, Jenyns moved to Darlington Place, and later Belmont, marrying again in 1862.

He was founder in 1855, and long time President, of the Bath Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club, whose proceedings abound with his papers. He donated his library of more than 2,000 books, including numerous manuscripts, scrap books and his correspondence. Jenyns also left the Institution a large collection of shells and an impressive herbarium.

An interest in meteorological matters had begun early when he noticed Gilbert White’s comments about the link between animal behaviour and weather. From this he developed his own ideas and, much later, he read a paper on the subject to the Physical Section of the British Association at their annual meeting in Bath in 1864. The paper aroused considerable interest and he followed this by setting up a meteorological observatory in the Institution Gardens in 1865, which he monitored regularly, analysing and summarising the readings in 1875 and 1885.

Surprisingly with his chosen subjects, Jenyns felt he could not draw (unlike the rest of his family) and he always preferred not to attempt to study two subjects at once. In his early years, he expressed a disdain for four things that might so easily have been part of the lot of a rural vicar: “Sporting, Farming, Politics and Magisterial Business” and his focus and studying instincts were confirmed by one of his servants who noted “My master, you know, is such a thinking gentleman”. Towards the close of his career he was held in honour as the patriarch of natural history studies in Great Britain.

Leonard Jenyns is commemorated today at BRLSI in the name of the Jenyns Room, the Institution’s main gallery space, which is used for art and museum exhibitions.