Beyond Beastly

By the 17th century people began to question how real these strange monsters were. The rapid progression of science and the discovery of curious animals in distant continents saw a cognitive shift from a chaotic mythological world to a catalogued and ordered one. Though dragon has been supplanted by dinosaur, unicorn by rhinoceros, and sea monster by plesiosaur and giant squid, we still reach for monsters to fulfil the role of adversaries and warnings.

Such creatures were seriously feared at a time when the boundary between superstition and reality was blurred. Is it not the case that even now we seek to explore perceived and real threats through the medium of story and imagination?

The malevolent monsters of our myth and legends were archetypes of our feared predators, but also metaphors for overcoming perils and tempering our own destructive potential.

What mythical beast can be warded off by carrying a weasel?

Is a unicorn different from a rhinoceros or a narwhal?

What did St Keyna do to the venomous snakes of Somerset 1600 years ago?

The world was an even more mysterious place a few hundred years ago. People really used to believe in unicorns and dragons.

Perhaps you would too if you heard stories about weird creatures from remote corners of the earth, before travel was easy and before most people could read, let alone watch YouTube!

Jump to a particular beast:

In 1612 Wolfgang Franz, a German theologian, wrote a book on animals focusing on their moral, aesthetic, and miraculous qualities.

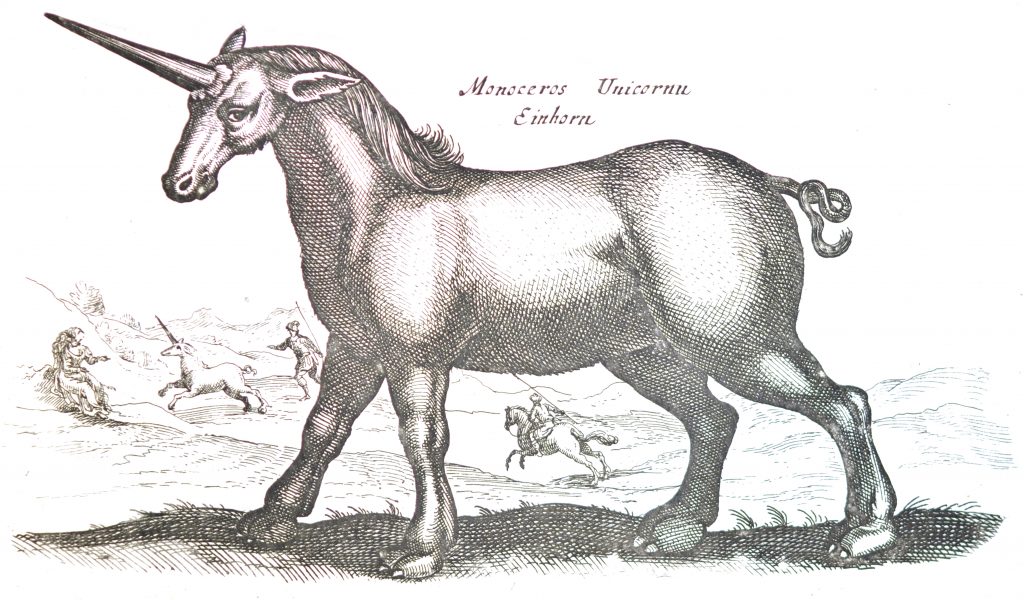

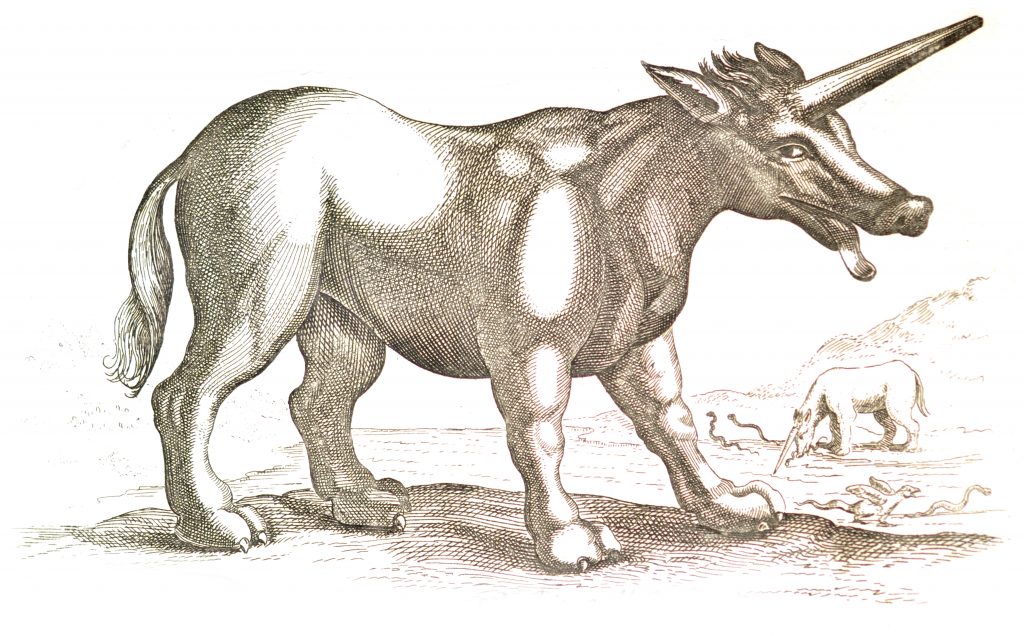

He wanted to provide accurate information for religious preachers to use as examples in their sermons. Franz included comments on mythical creatures as well, and insisted the unicorn is a regularly occurring animal in nature – with reference to what he considered to be its Biblical description.

Other mythical creatures he describes are the behemoth, leviathan, sphinx, phoenix, griffin, harpy, mermaid, dragon and basilisk.

The History of Brutes, Wolfgang Franz, 1616 (English edition 1679)

Pseudodoxia Epidemica, Thomas Browne 1672

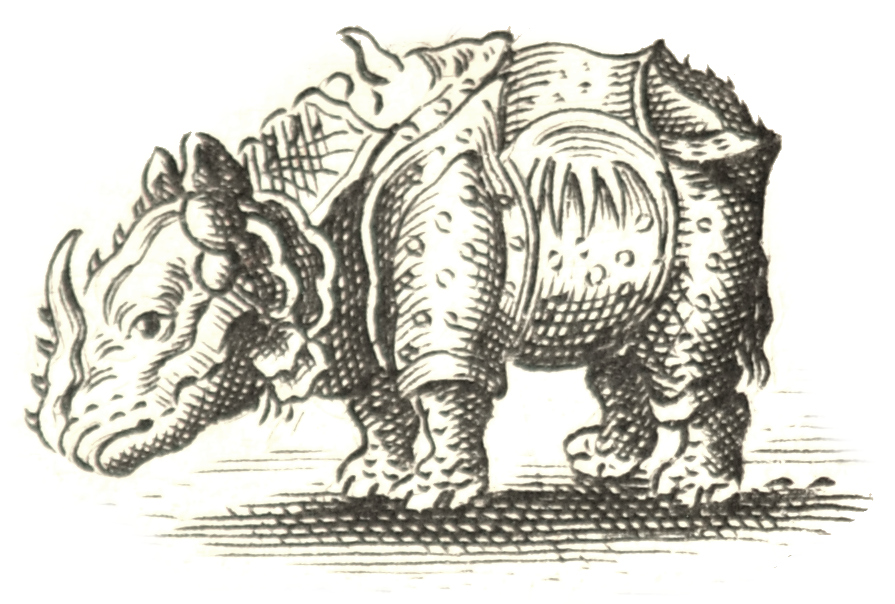

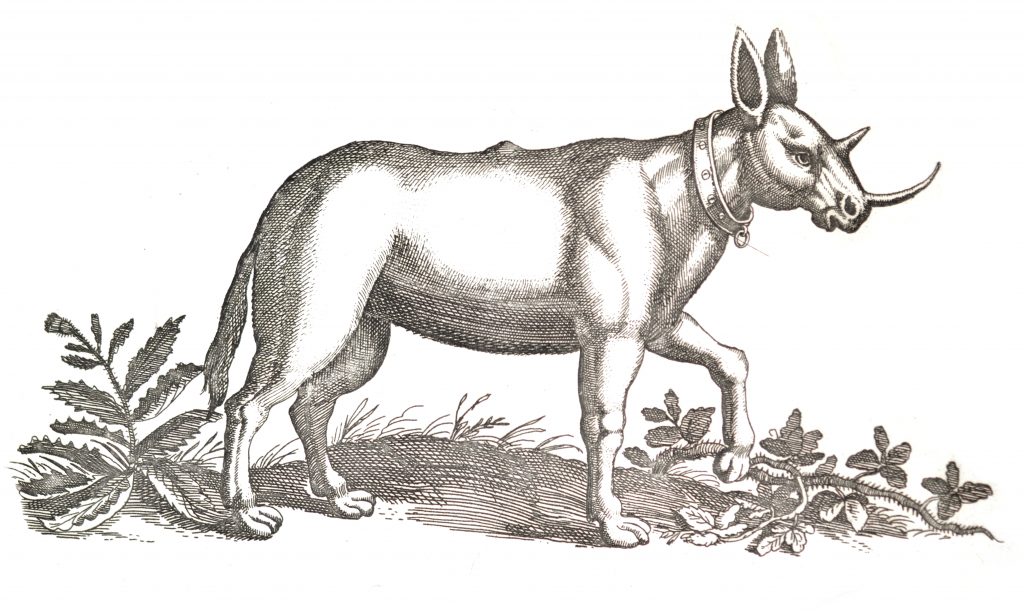

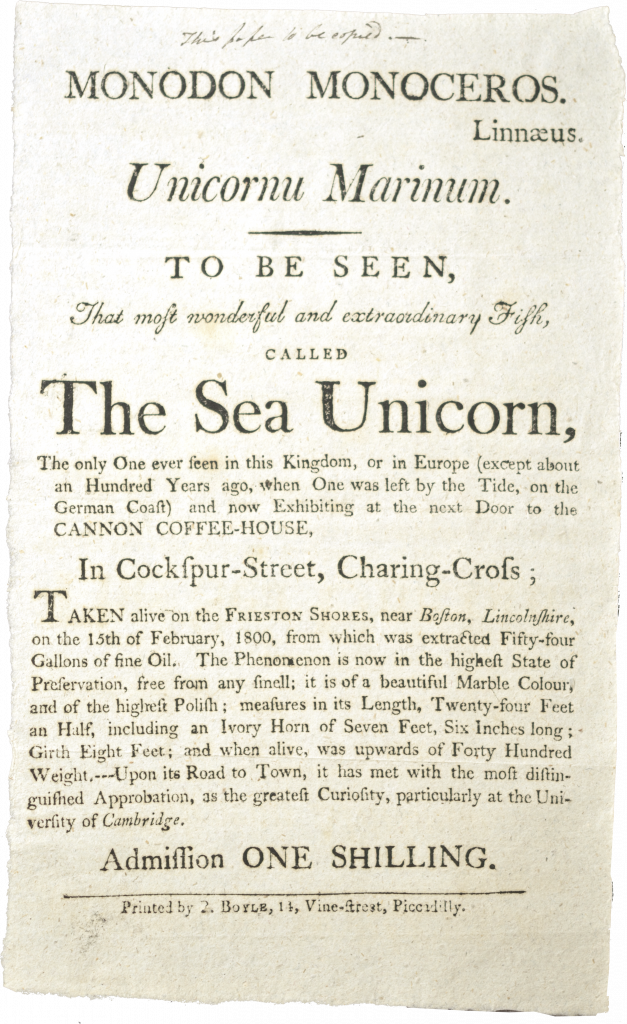

Confusion about the unicorn and its horn existed for centuries. As early explorers searched for the mythical unicorn, they encountered all kinds of possible candidates. Marco Polo, travelling through China, encountered a single-horned animal which he could only believe was a unicorn, although in fact it was an Asian rhino – and rather uglier than a unicorn was supposed to be.

By the 19th century it was understood that horns such as this one were actually tusks that came from the Narwhal, an arctic whale named Monodon monoceros (Linnaeus 1758) and that rhinoceroses were distinct creatures that included extinct ice age species. The woolly rhinoceros was one of the Pleistocene megafauna which walked into Britain across the ice-age steppe, when sea levels were much lower.

Narwhal tusk, donated by Miss Clephane of Gay Street Bath in 1881 and Wooley Rhinoceros Tooth from Wookey Hole, Somerset, donated by John Kelway, Esq., Chatham House, Prior Park Road, Bath in 1892.

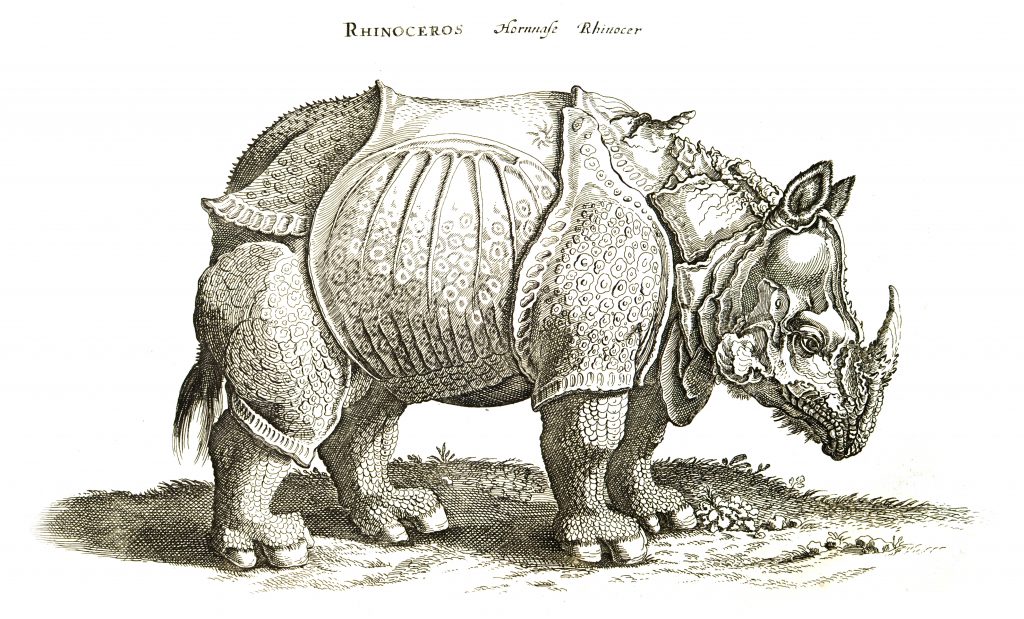

Albrecht Dürer’s compelling woodcut of a rhinoceros was made in 1515. A spiral horn grows out of its back and seemingly it wears a suit of armour. This image influenced people’s idea of the creature for two and a half centuries and was much copied by other artists over the years, as seen here. Dürer had never set eyes on the real animal and based his drawing on a written description and someone else’s sketch.

Dürer’s rhino and and numerous unicorns are depicted in ‘Historiae naturalis de quadrupedibus libri’ by Joannes Jonstonus, with engravings by Mathias Merian, 1657.

It was once widely believed that helically grooved ‘horns’ in early museum collections belonged to the mythical unicorn. Eventually they were identified as the tusk of the male narwhal, a whale living in Arctic waters. This tooth can grow up to three metres long and its natural spiral shape influenced the way that unicorn horns have been depicted from medieval times.

These tusks were rare finds, occasionally brought back by mariners from northern lands. They were highly valued and reputed to neutralise any poison if ground up and put in liquid. Queen Elizabeth 1st paid the equivalent of a third of a million pounds for a single horn.

Albertus Magnus describeth one ten foot long, and at the base about thirteen inches compass. And that of Antwerp is not much inferior to it; which best agree unto the descriptions of Sea-Unicorns; for these are of that strength and bigness, as able to penetrate the ribs of ships.

Thomas Brown Pseudodoxia 1658

The unicorn is no longer the shy, magical creature of the deep forest but has now been put to work selling anything vaguely glittery, shiny or colourful — in fact anything that can be

‘unicornified’.

Femurs of moa (Dinornis sp.) and the dried foot of an emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

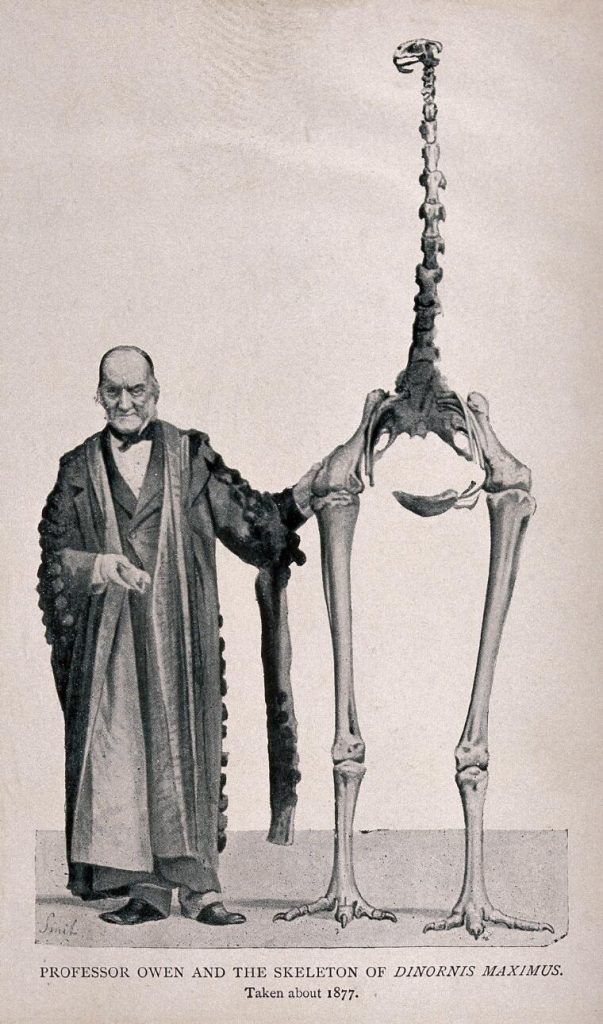

Richard Owen, Victorian palaeontologist and first superintendent of the Natural History Museum, examined a small bone fragment sent from New Zealand and predicted it belonged to a flightless bird far larger than any known to be living now. He named it Dinornis, meaning ‘terrible bird’, and was able to reconstruct a full skeleton after receiving more bones a few years later.

Maori legends describe huge birds roaming the islands

The moa were giant wingless birds living in the forests of New Zealand. They became extinct around 1400CE through overhunting after the arrival of the Polynesian settlers. Prior to the arrival of humans the moas only predator was the massive Haast’s eagle, larger than today’s most powerful living eagles.

Mythical birds from ‘Historiae naturalis de avibus libri’ by Joannes Jonstonus with engravings by Mathias Merian published in parts between 1657 and 1660.

From ‘Pseudodoxia Epidemica or Enquiries into very many received tenents and commonly presumed truths’

Thomas Brown 1646

The phoenix, that famous bird of Arabia; though I am not quite sure that its existence is not all a fable. It is said that there is only one in existence in the whole world, and that that one has not been seen very often.We are told that this bird is of the size of an eagle, and has a brilliant golden plumage around the neck.

Pliny the Elder, ‘Natural History’ AD 77

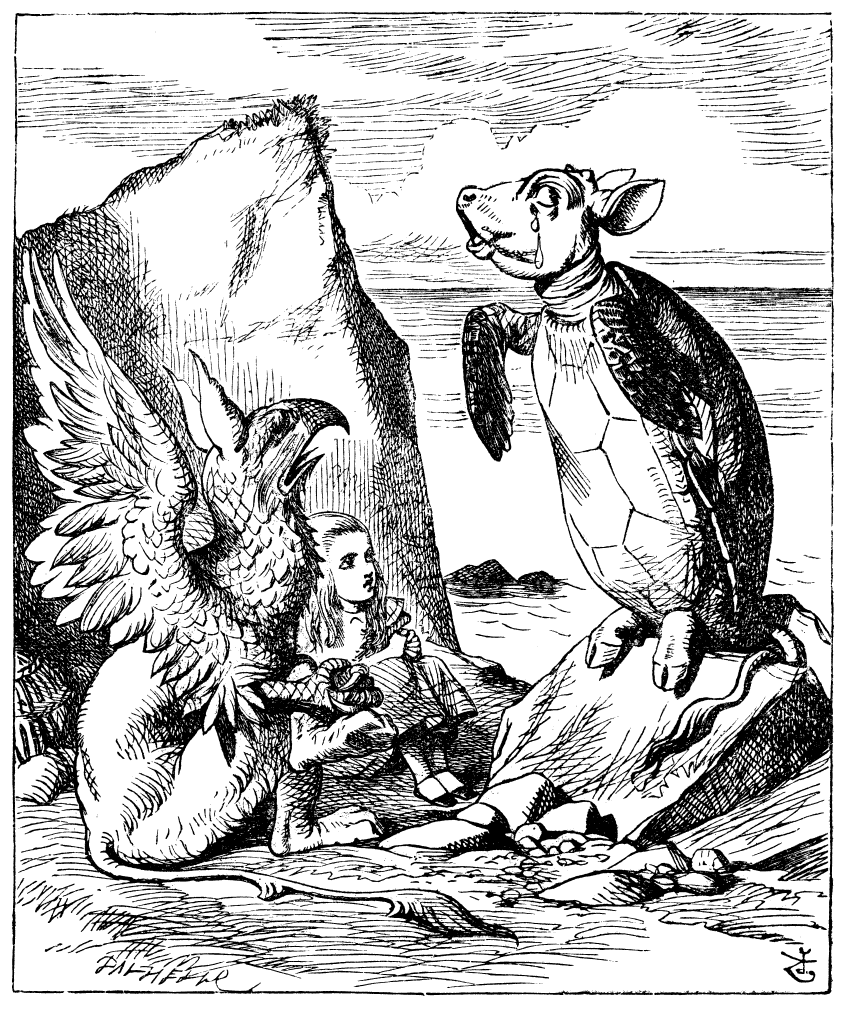

Alice did not quite like the look of the creature…

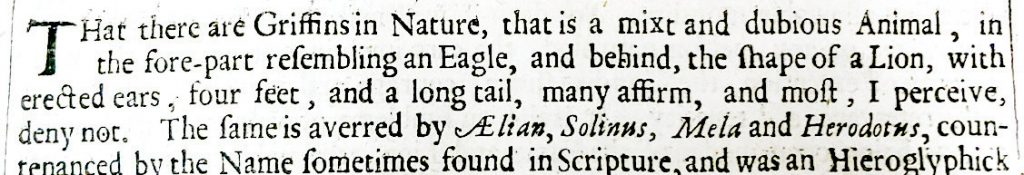

Alice was wise to be cautious as the griffin was known to be a fearsome, predatory beast.

‘Alice in Wonderland’ Lewis Carroll, 1865

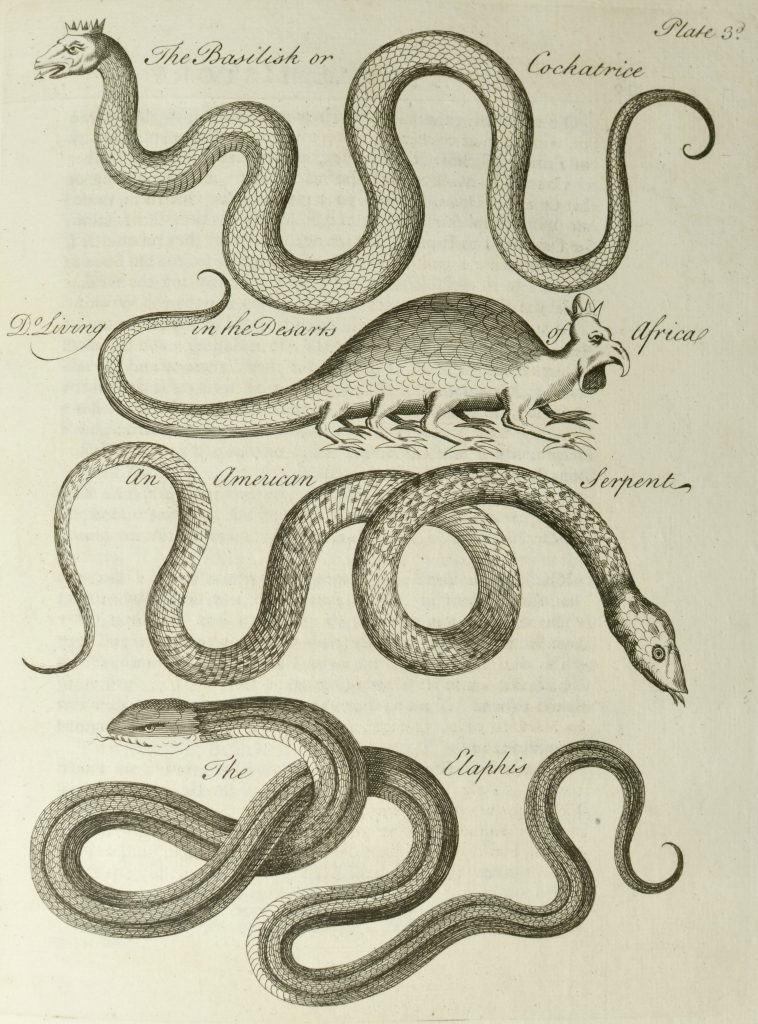

The basilisk, or cockatrice, was believed to hatch from a snake’s egg and has long been an object of complete terror.

Its touch, breath and particularly its malevolent gaze were thought to be lethal. Such was the strength of its poison it could flow up a weapon and destroy the bearer. Travellers were advised to carry a mirror and a weasel for their protection. In later times it acquired the body parts of a rooster.

Cockatrice from ‘Historiae naturalis de avibus libri’ by Joannes Jonstonus with engravings by Mathias Merian published in parts between 1657 and 1660.

It is gross in Body, of fiery Eyes and sharp Head, on which it wears a Crest, like a Cock’s Comb. Its poison infects the Air so that no Animal can live near it. They are bred in the Solitudes of Africa. It does not, like other Serpents, creep on Earth.

‘Natural History of Serpents’ Charles Owen 1742

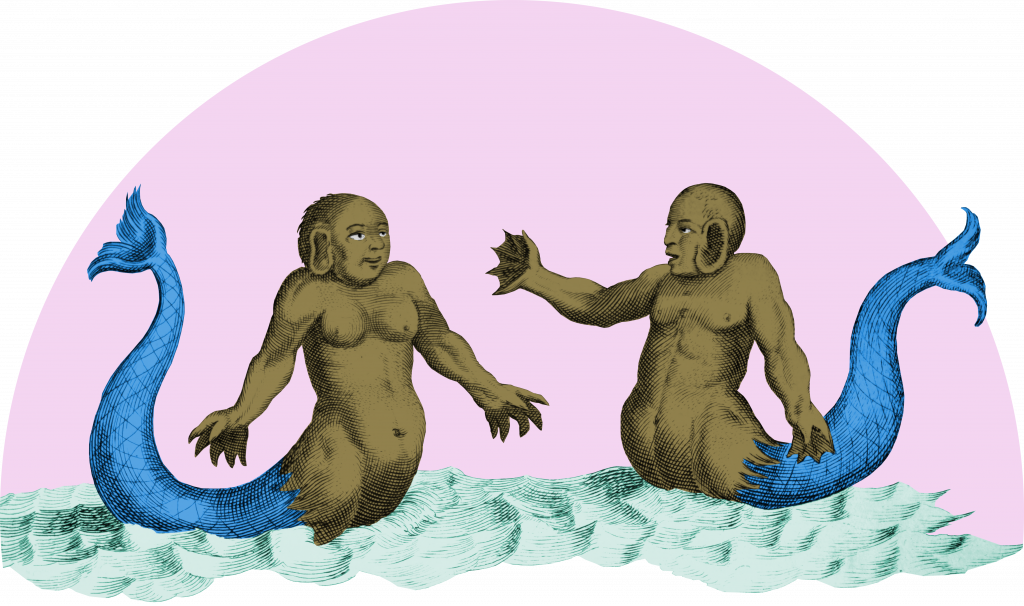

Illustration of mermen from a widely read 17th century work of natural history in which mythical beasts, taken from Biblical and ancient sources, are presented next to realistic animals.

Historiae Naturalis, Joannes Jonstonus 1657

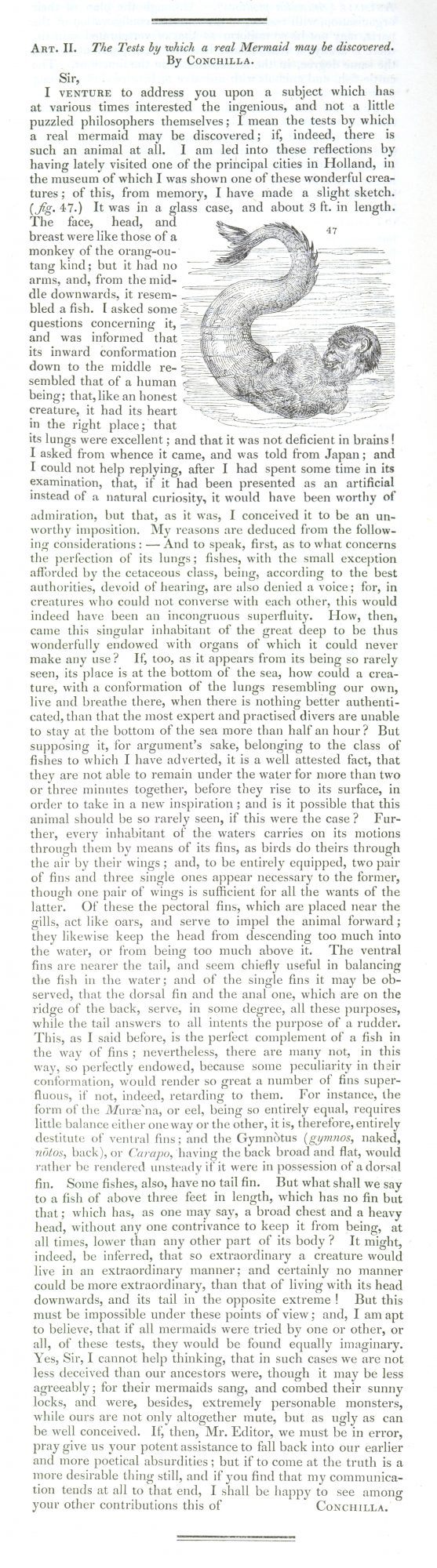

Fake or Fiction?

Resembling a mummified merman, this ‘creature’ was described as a ‘Japanese Monkey-fish’

This curiosity was assumed to consist of a monkey head and fish’s tail, but recent scans and Xrays by Horniman Museum revealed a combination of materials: fishes’ teeth and fins, wood, clay, papier-mâché and chicken claws. It was likely made to supply a late 19th century tourist market. In Japan ancient mermaid relics are recorded in Shinto temples.

Photo: Horniman Museum and Gardens

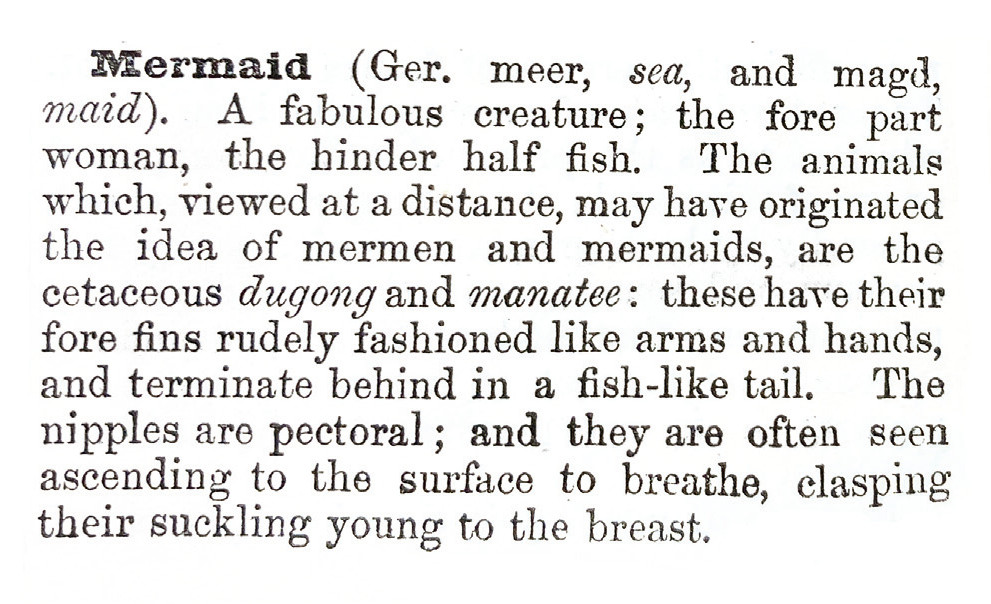

A comic, pseudo-scientific interrogation of the existence of mermaids

Article from Magazine of Natural History 1829

A few creatures can regrow their damaged body part.

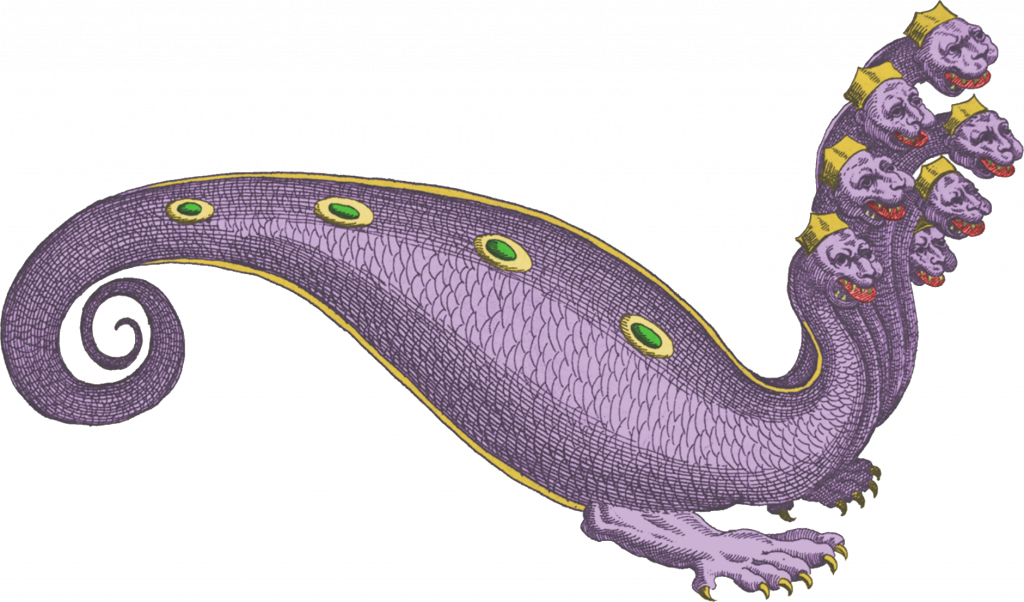

The Lernean Hydra, a swamp-living mythical beast, had two strategic weapons: poisonous blood, and multiple turbo-charged heads which could attack from every angle.

As soon as one head was cut off, a new one grew back. The Greek hero Heracles, for one of his twelve labours, destroyed the Hydra by scorching the open stumps of its necks with a firebrand, using arrows dipped in its blood to kill new foes. After the battle the goddess Hera raised the beast into the sky to form the constellation Hydra.

Greek jar, Heracles and the Lernian Hydra 480BC

British Museum

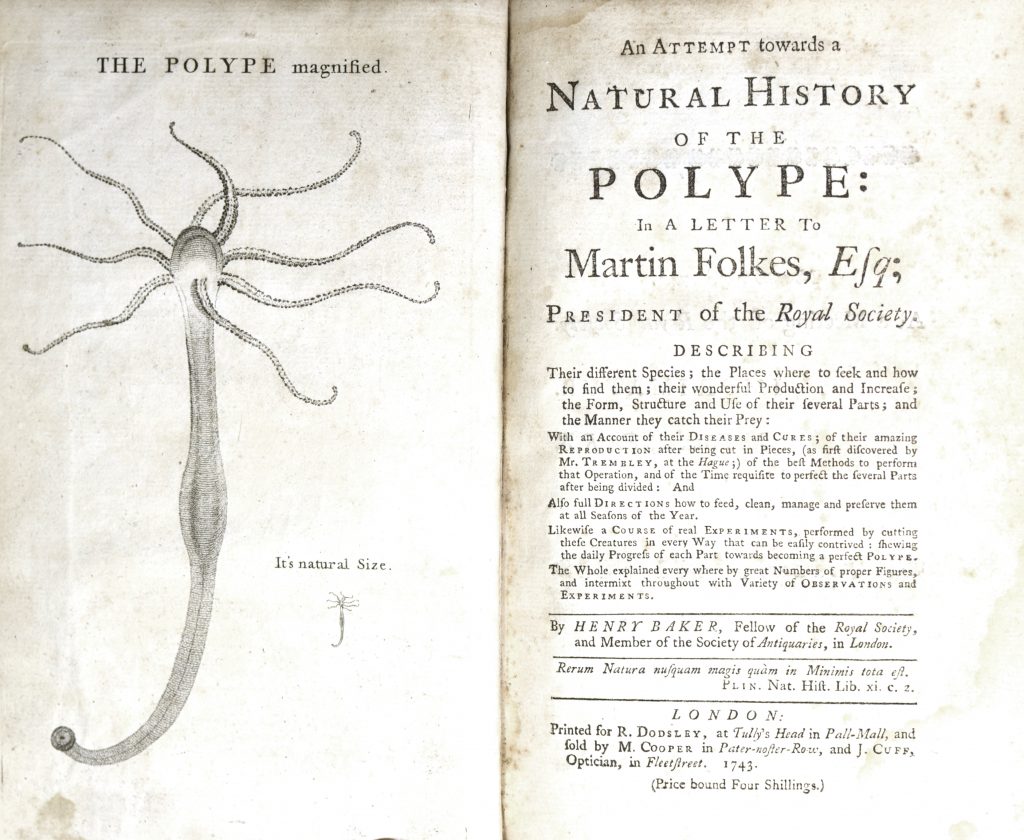

The hydra or polype, a tiny pond dwelling organism, became an object of great fascination and debate during the 18th century.

Animal or plant? Detailed experimentation established that cutting the hydra in half caused the remaining piece to regenerate completely.

“A polype cut transversly in three parts, requires four or five Days in Summer, and longer in cold Weather for the middle piece to produce a Head and Tail, and the Tail-Part to get a body and Head.”

Natural History of the Polype Henry Baker 1743

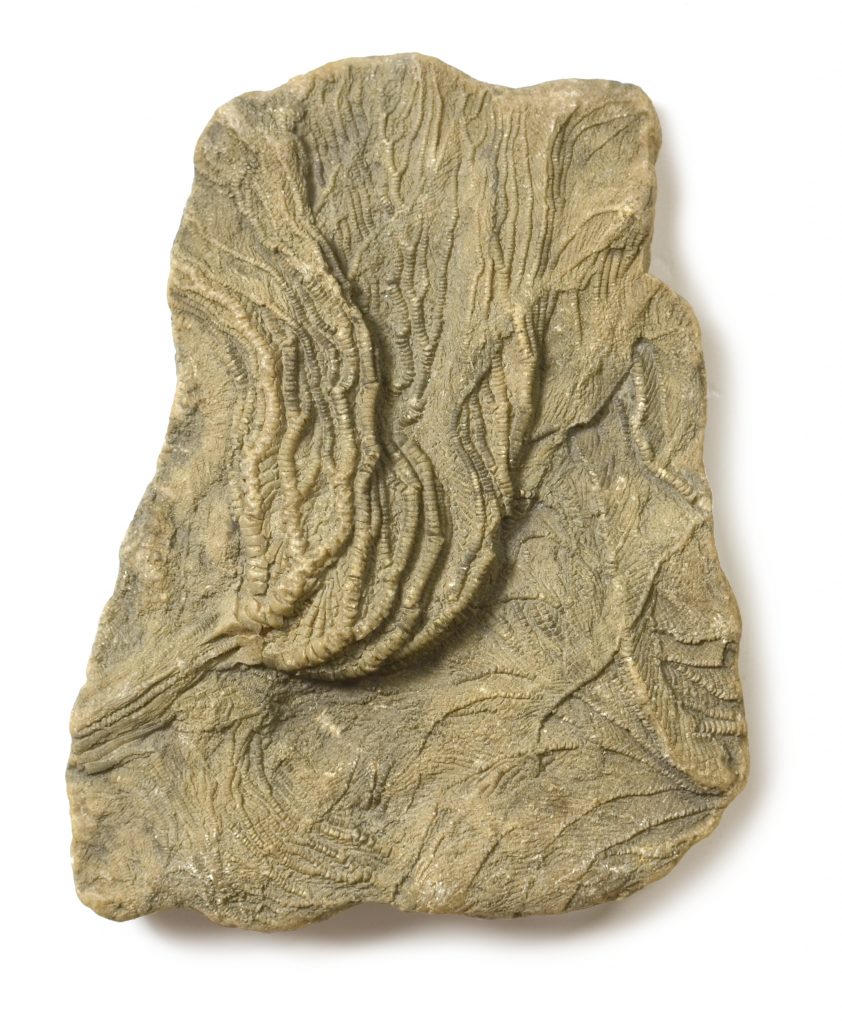

The fossil crinoid, though commonly known as ‘sea lily’, was actually an animal and not a plant. Related to sea urchins and starfish, the crinoid – like the hydra – has the ability to regenerate most of its organs.

Fossil crinoid, Lower Jurassic

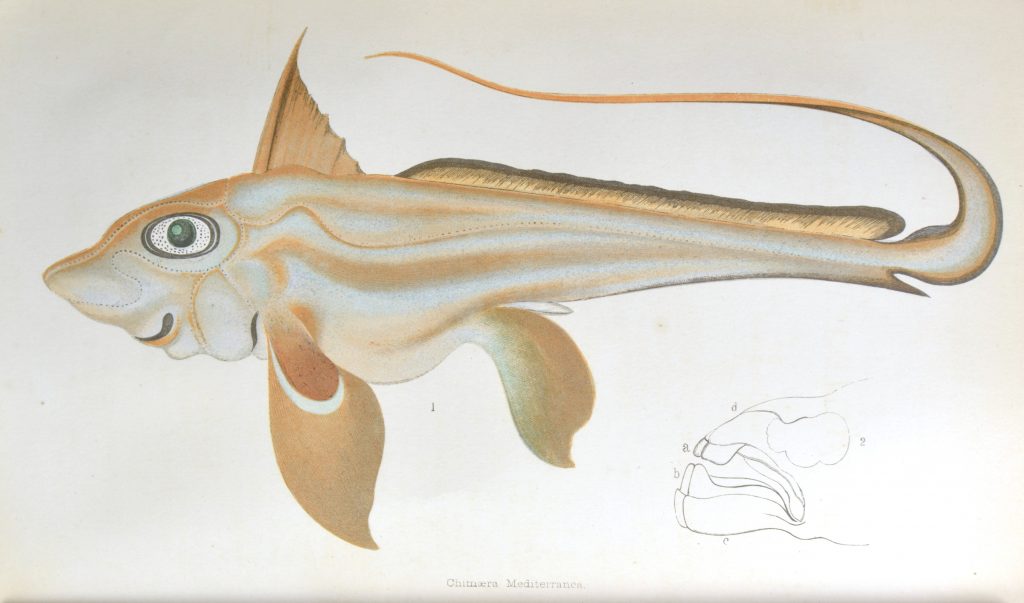

Chimera fish: the naming of parts

The early naturalists who named this family of fishes may have thought that the network of lines on its body suggested it had been stitched together from parts of other creatures. Other names for chimera fish are the rat fish, spook fish, rabbit fish, elephant fish and ghost shark.

Illustration from The Intellectual Observer 1867

The term ’chimera’ has come to mean any creature with a ‘beastly blend’ of incongrous parts.

Modern science can now create a real chimera. In 2017 embryonic human cells injected into a pig embryo were implanted into a sow, surviving for 28 days. This was the first time human cells were successfully grown in another animal, raising the possibility that human organs could be grown in other animals for transplantation into humans. Recently a pig heart was implanted into a living human – sadly the patient only survived two months.

Dictionary of Science, Literature and Art, 1867

The Greek hero Bellerophon battles the monstrous Chimera

Greek cup J. Paul Getty Museum

Giant marine reptiles, the ‘sea dragons’ of the Jurassic seas, were fierce predators (top)

Temnodontosaurus was a particularly fiercesome ichthyosaur, hunting in the deeper areas of the Jurassic oceans between 200 and 175 million years ago. It had teeth shaped like blades and an eye the size of a football, especially suitable for hunting in the deeper areas of the ocean.

A recent Temnodontosaurus discovery in 2021 was the Rutland ‘sea dragon’, the largest ichthyosaur ever discovered in Britain, measuring over 10 metres long.

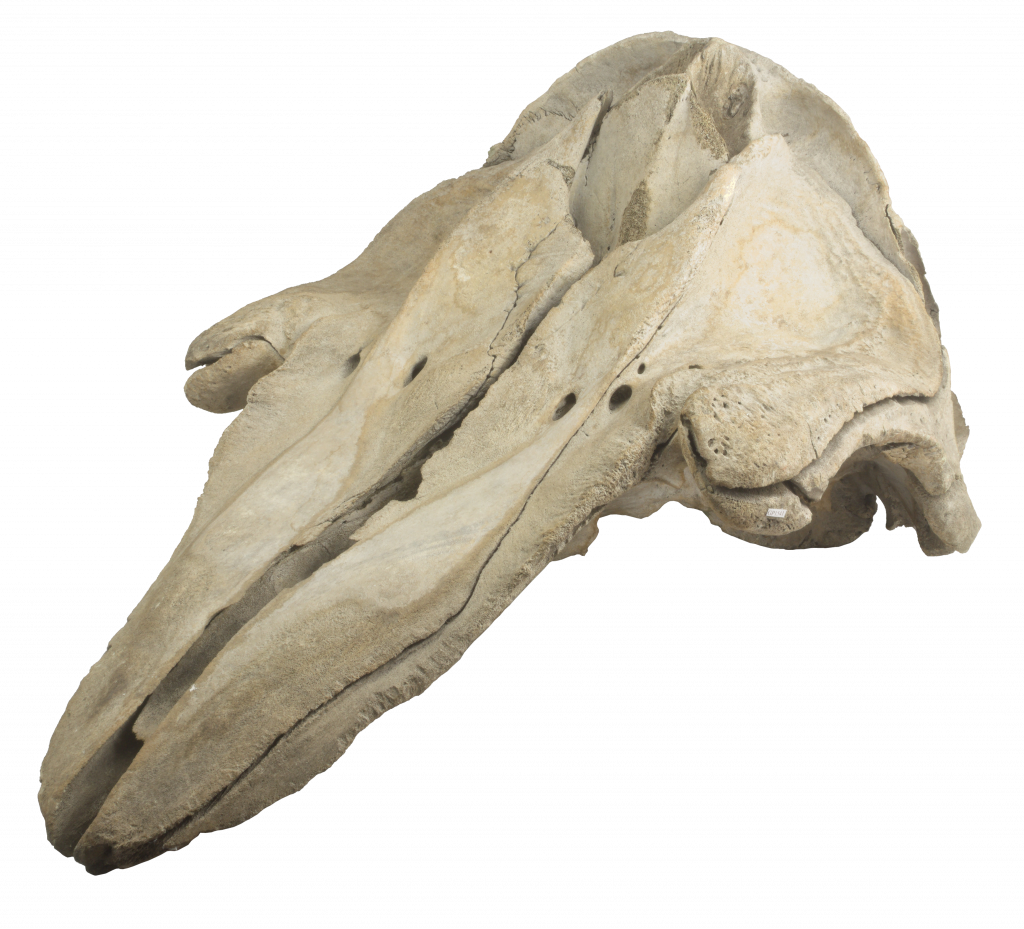

Lower jaw of Temnodontosaurus

A monstrous meal (middle)

Even for the giant marine reptiles of Jurassic seas, there was often a bigger, hungrier monster out there.

The rear limb bone of this 4½ metre long plesiosaur has been crushed by the bite of a super-sized predator. The tooth marks are clearly visible.

Limb bone of plesiosaur

The giant shark Megalodon was the one of the largest marine creatures ever to live (bottom-right)

It survived for 13 million years before going extinct. Three times the size of a modern great white shark, it snacked on whales with its enormous serrated teeth.

A megalodon’s teeth are the only fossil parts we find today, but as it lost a set of teeth every couple of weeks, some 40,000 might fall onto the ocean floor during its lifetime.

Three megalodon teeth

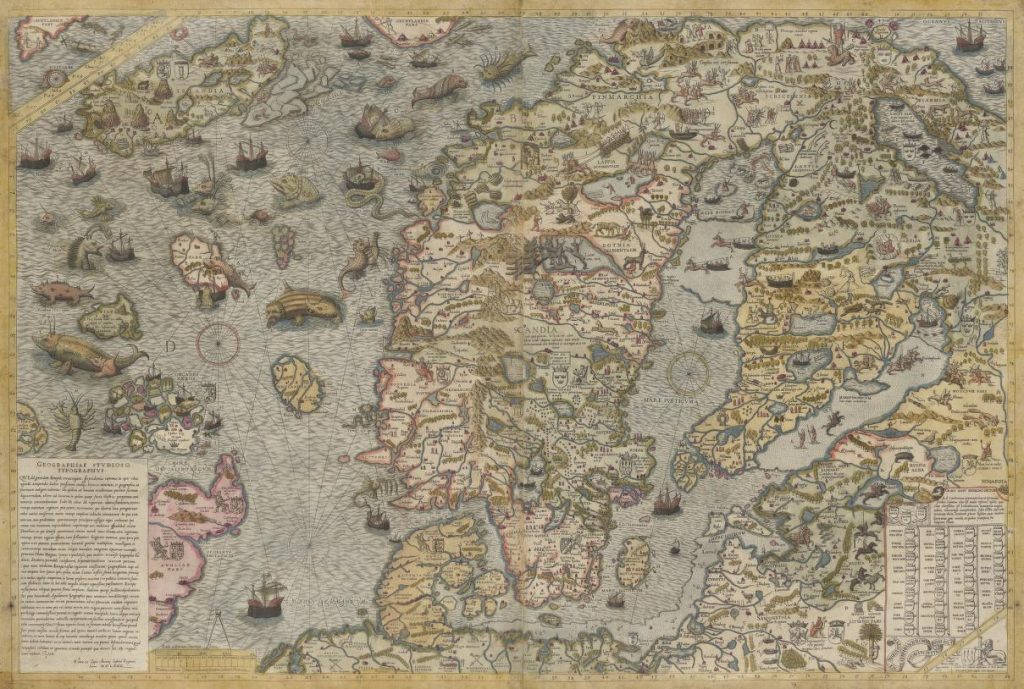

In the sixteenth century the world’s oceans were still mostly unexplored.

Depictions of sea monsters and mythological beasts on early maps warned of unknown dangers. Sailors returned with stories of mysterious encounters at sea, perhaps prompted by sightings of whales, walrus, squid or manatees. From time to time, the decomposing carcass of an unknown creature might be thrown up on shore, prompting wild speculation as to its identity.

A 16th century map of the Norwegian seas by Olaus Magnus featured an array of hideous beasts. Magnus was the Archbishop of Sweden; his accounts of travels around Scandinavia were widely read and his drawings copied for the next two hundred years. Sea serpent sightings persisted through the 19th century.

Image from the World Digital Library

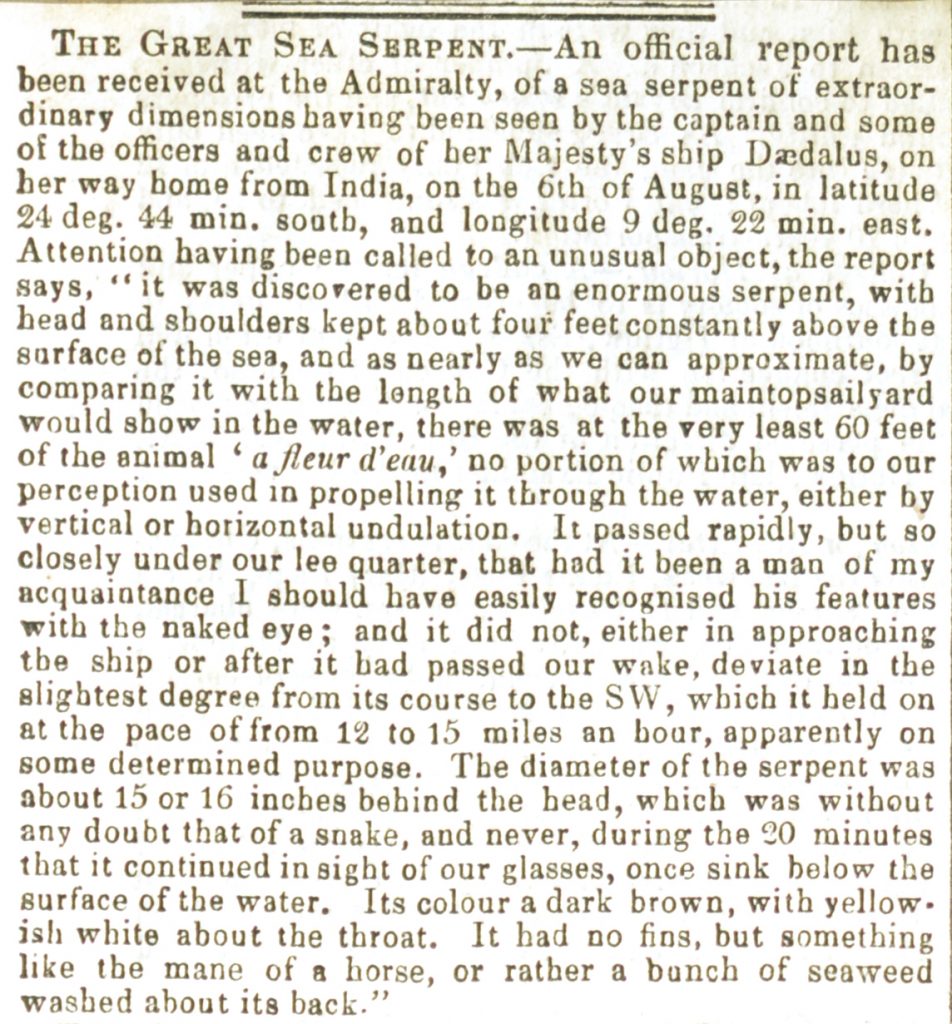

A report from the captain of HMS Daedalus, describing an encounter with a sea serpent off the coast of South Africa, appeared in newspapers in October 1848.

If a gigantic sea serpent actually exists, the species must have been perpetuated through successive generations, from its first creation and introduction in the seas of this planet. Conceive, then the number of individuals that must have lived and died and left their remains. A serpent, being an air-breathing animal, dives with an effort and commonly floats when dead, and so would the sea serpent, until decomposition or accident had let out the imprisoned gases. Then it would sink and be seen no more until the sea rendered up its dead.

Palaeontologist Richard Owen’s counter-argument (above) was based on a lack of physical evidence of such monsters. He concluded the creature was probably a large seal.

Illustration of Squid and Octopus

The Genera Vermium of Linnaeus, plate of octopus and squid, James Barbut 1783

In the first edition of Systema Naturae (1735), Carl Linneus classified the kraken as a cephalopod ‘Microcosmus marinus’. Thus a sea monster passed from myth to science in the biological form of the giant squid, about which very little is known, even today.

Real sea creatures like whales and dolphins were poorly understood at the time when it was believed mythical monsters inhabited the oceans. Glimpsed by superstitious seafarers, they were seen as malevolent forces and were greatly feared.

Skull of Risso’s dolphin, living in the last interglacial 125,000BCE, from Twerton Gravel pits

Model of a megalosaurus, one of the dinosaurs made for the 1854 Crystal Palace Park

Dinosaurs can appear like hybrids of mythical dragons and modern-day lizards and crocodiles. With few actual fossil bones to study for this reconstruction, Hawkins may have taken inspiration from a giant reptile like the monitor lizard. He designed a squat, bulky form with a dragging tail and four sturdy limbs, but fossil evidence later suggested megalosaurus stood on two legs, with small forearms and a deeper, less crocodile-like skull.

Model by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins under the direction of Richard Owen in 1854

Did fossilised bones unearthed in the past fuel the dragon myth?

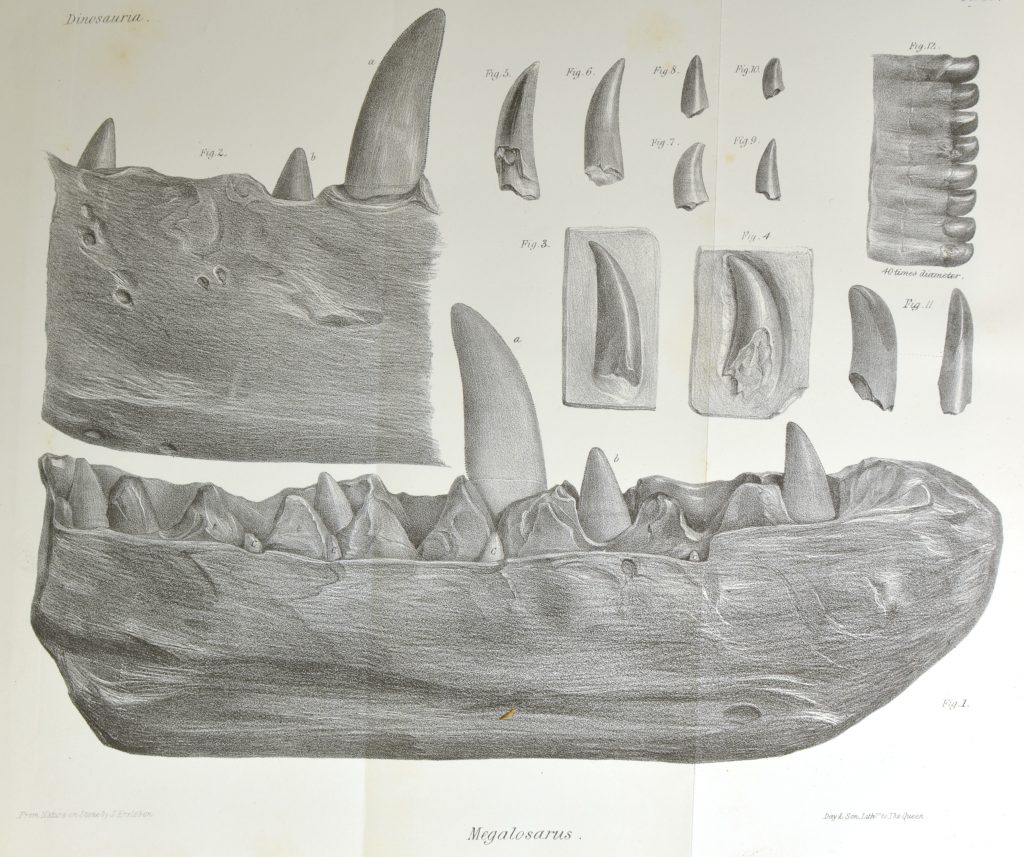

‘Dragon’ bones, teeth and horns were believed by Chinese apothecaries to cure many ailments. Such bones were known about centuries before palaeontology became a serious discipline, advanced by the likes of Richard Owen (who coined the word ‘Dinosauria’ meaning ‘Terrible Lizards’ in 1842).

With only a few fragments to go on, including the specimen jaw illustrated with its vicious blade-like teeth, Owen named the Megalosaurus as a four-footed carnivore with a reptilian dragon-like form.

A History of British Fossil Reptiles Richard Owen 1849

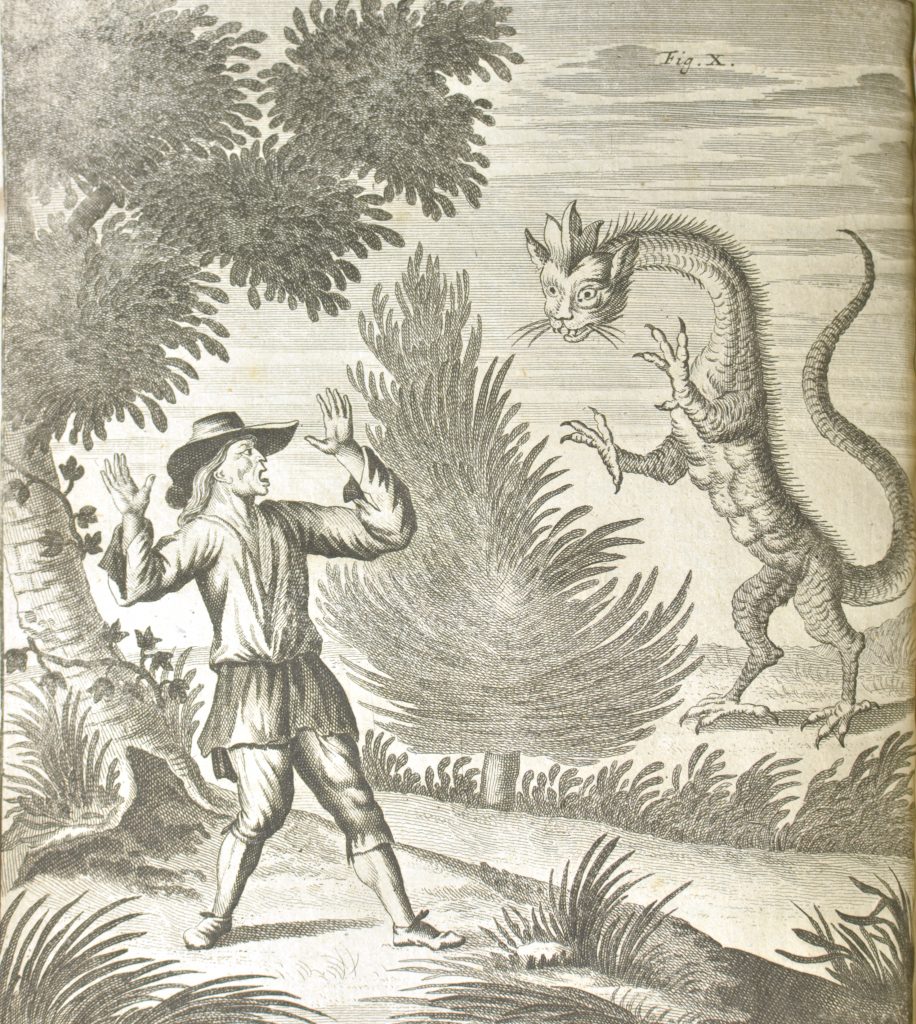

Belief in strange creatures inhabiting forests and caves persisted over centuries in the remote areas of Alpine Switzerland.

This travel book contains a whole chapter recording legendary encounters with strange creatures.

‘In the summer of 1717 Joseph Gackerer encountered an animal with the head of a cat, with large eyes, a thick body and breasts pending from the body. The entire body was covered by scales. The man touched it with a stick: it was soft and full of poisonous blood.’

Itinera per Helvetiae Alpinas Regiones J.J.Scheuchzero 1723

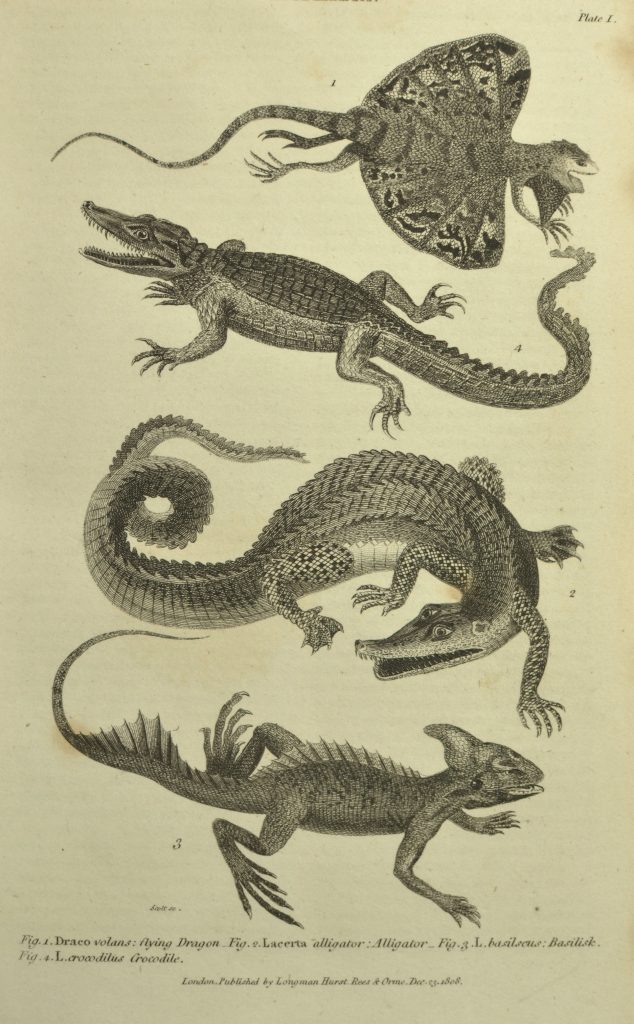

Four dragon-like creatures described as ‘Flying Dragon, Crocodile, Alligator and Basilisk’

Crocodiles and lizards may have been the source of primitive ideas about dragons. Nineteenth century palaeontologists asked themselves whether existing reptile species could provide a model for interpreting recent discoveries of supersized fossil teeth. But scaling up could lead to gross miscalculations: an early estimate of the size of the iguanodon using this method put it at over 30 metres long.

The British Encyclopedia, William Nicholson, 1809

There is great antipathy between Elephants and Dragons. The first thing a Dragon doth, when he takes an Elephant, is to entangle his feet in a knot; after that the first part he wounds is his Ear, which he wounds until the blood spout out, for the Dragon being a very hot Creature drinks the blood of the Elephants, which he knows is cold.

After they have killed the Elephant by sucking his blood, they never touch the body; the Dragon will drink himself drunk with his blood, and they will drink until they burst themselves, so that the Conqueror and Conquered die both together.

The History of Brutes Wolfgang Franz 1616

A dragon floats among clouds on a Japanese Takaoka kettle made of iron, 19th century

Dragons in oriental culture are powerful spirit creatures with control over wind and water, bringing fortune and prosperity, and a far cry from the aggressive fire-breathing European dragons which lurked in deep caves and guarded a heap of treasure.

A carved olive wood paperweight from the Holy Land depicting St George and the Dragon

The medieval dragon, sporting leathery wings and long muscular tails, was absorbed into a Christian narrative, and came to symbolise the defeat of diabolical or pagan forces by a stronger heroic power.

Snakestones

A legend relates that St Keyna, the daughter of a Welsh king, lived close to the Avon in the 5th century, in a marshy area infested with snakes.

It was believed that through prayer she transformed the snakes into stone.

These coiled bodies, found in the local fields around Keynsham, are what we now know to be fossil ammonites.

In fact the ammonites were laid down in the shallow muddy seas of the Jurassic, 200 million years ago. They went extinct at the same time as the dinosaurs.

Myths, Scenes, and Worthies of Somerset, Charlotte Boger 1887

Dictionary of Science, Literature and Art, 1867

The heads of these so-called snakestones were never found of course. It was part of the superstition to believe they were destroyed when the died.

So enterprising dealers in fossils began a thriving trade in ‘restoring’ snakestones by carving heads on them.

In Elizabethan England snakestone brooches carved from jet were highly

prized.

Serpents are the most unsettling of creatures, inducing universal feelings of fear and awe, and are depicted in cultures around the world.

The shedding of skin, the slithering motion, staring eyes and sometimes venomous bite have made them potent symbols, representing many things – renewal, fertility, healing, immortality and death.

A hand grasping the head of a snake on what was reputed to be a ‘witch’s stick for smelling-out victims for sacrifice’ Central Africa.

It is likely that most of the mythical beasts in this exhibition do have a basis in real biology, though their forms and behaviours have changed with the course of history. In their early history their precise appearance was not considered as important as their symbolic qualities.

Others, like the basilisk and hydra, went on to give their names to newly discovered species, on the basis of shared characteristics.

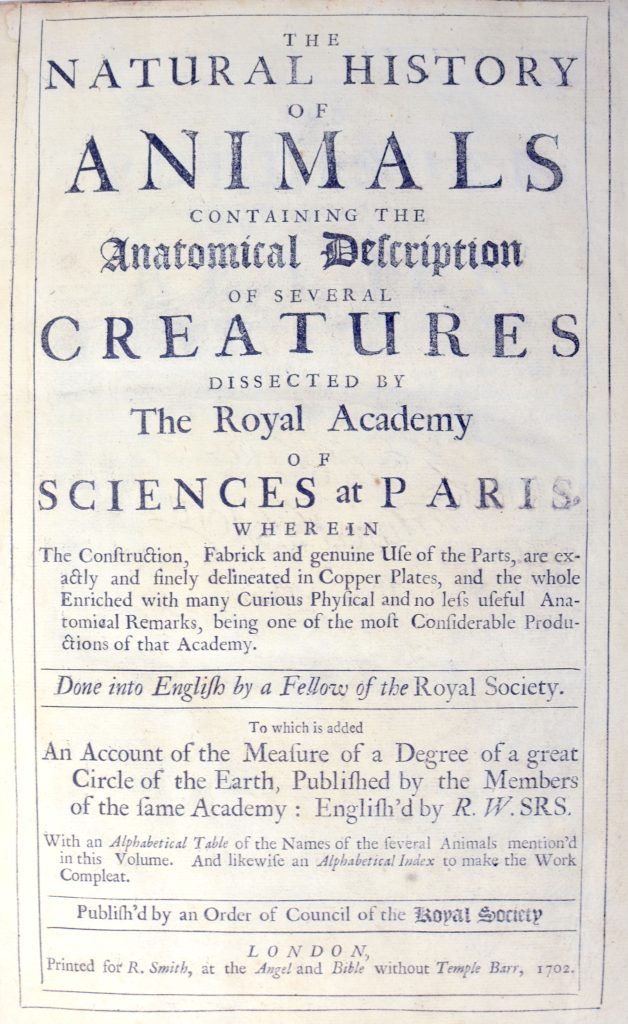

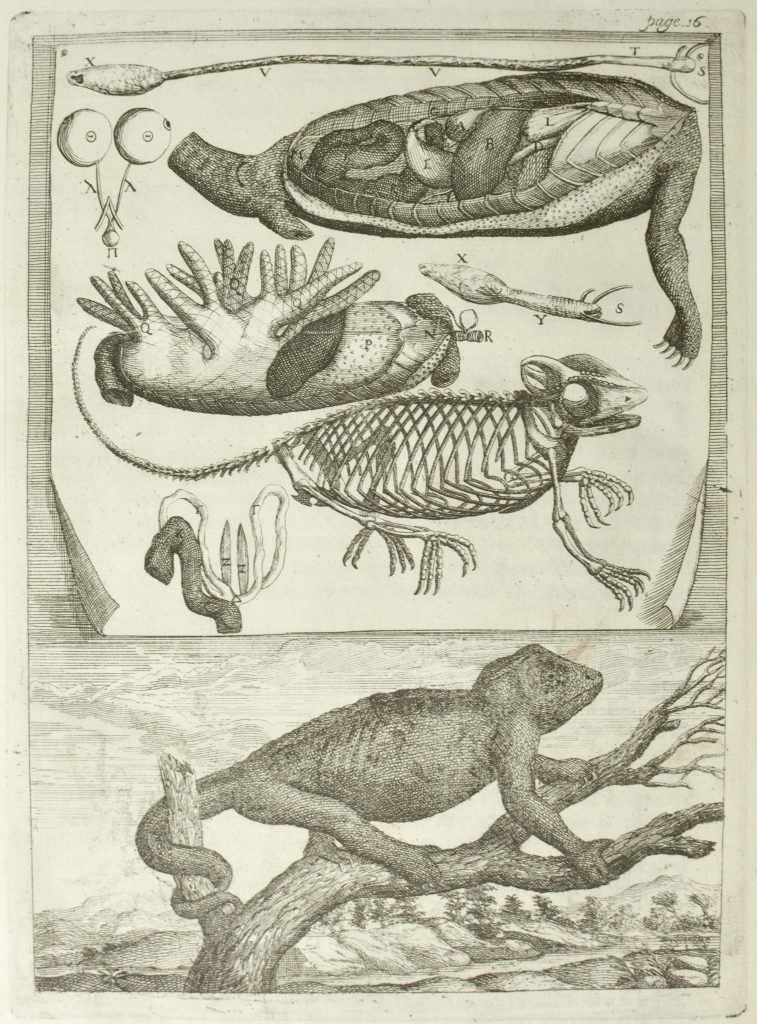

The natural history of animals containing the anatomical description of several creatures dissected, by the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris 1702

This book, published in England at the beginning of the 18th century, is an example of the shift from the fabulous encyclopaedic natural histories of scholars like Johannes Jonstonus (whose book has been shown elsewhere in this exhibition), to the more analytical science of the Enlightenment.

With a new emphasis on comparative anatomy, it describes the dissection of a selection of animals sourced from the menagerie at Versailles. Each is illustrated alongside its dissected parts, with details of digestion, respiration and vision.

Journal of a voyage to New South Wales, John White 1790

In the 18th century previously little known parts of the globe were opening up to Europe through long distance exploration, revealing a world of wonders. There was huge excitement at the strange, exotic creatures recorded from Captain James Cook’s three voyages to the southern hemisphere between 1768–1780.

Accurate illustrations became crucial to advancing scientific knowledge. Explorers like Cook hired scientists and artists to accompany their expeditions for the purpose of describing and drawing the flora and fauna they encountered. Returning to England, their sketches were engraved onto plates for mass-production to satisfy an ever-increasing audience of collectors and amateur artists.

Hurried sketches by ships’ officers were sometimes of dubious accuracy, which were then inaccurately copied back in England. Dried specimens sent back were poorly prepared.

However, such images may represent the only known record of a species for which no specimen has survived. Twenty eight mammals, part of that unique Australian faunal assembly, have become extinct since 1788.

The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, Arthur Phillip 1789

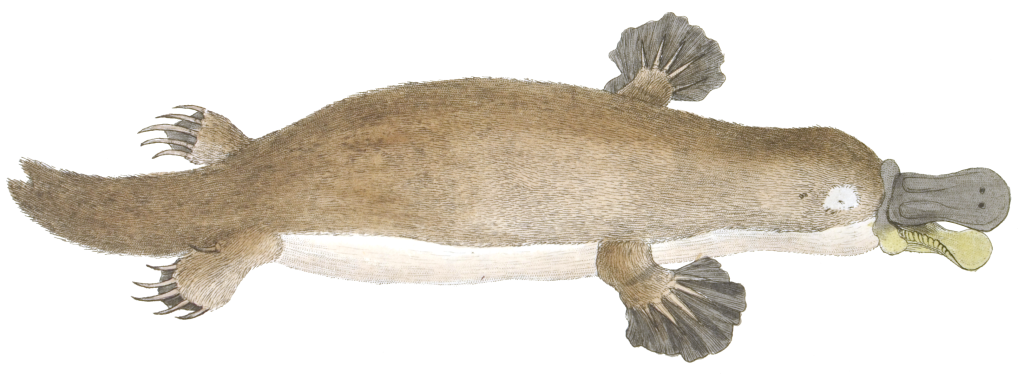

The Naturalist’s Miscellany was a compendium of beautifully engraved, hand-tinted plates of newly discovered species, published by George Shaw between 1789 and 1813.

Shaw published the first scientific description of the ‘duck-billed’ platypus. After this animal was first encountered in Australia in 1798, a pelt and sketch were sent back to England. It seemed too bizarre – a creature with characteristics of a bird, mammal and reptile. No other furry egglayer was known.

Initially it was thought to be a hoax (like the Japanese Monkey-fish/merman) with a duck’s beak sewn onto the body of a beaver-like animal. Shaw inspected the dried skin for stitches but decided it was genuine, giving it a name (‘Platypus’ meaning ‘flat-foot’).